Putting ‘Hobby Lobby’ in Context: The Erratic Career of Birth Control in the United States

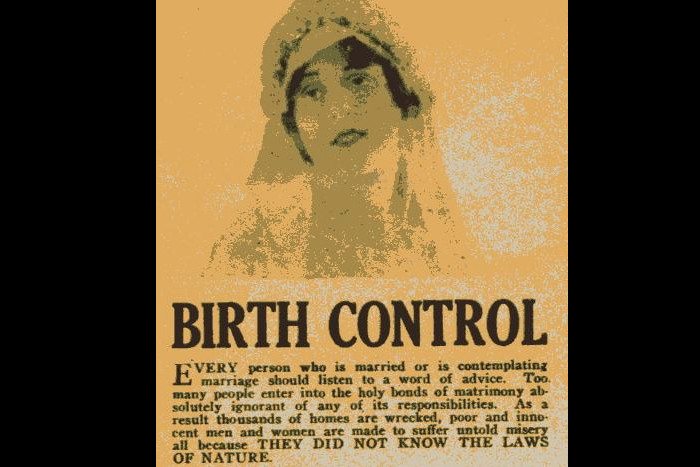

The contraceptive wars started with the notorious campaign in the late 19th century of the Postmaster General Anthony Comstock, who successfully banned the spread of information about contraception under an obscenity statute.

Cross-posted with permission from The Society Pages.

Read more of our coverage on the Hobby Lobby and Conestoga Wood cases here.

Nearly 50 years ago, in the 1965 Griswold v. Connecticut case, the Supreme Court declared birth control legal for married persons, and shortly afterwards in another case legalized birth control for single people. In a famous study published in 2002, The Power of the Pill, two Harvard economists reported on the dramatic rise in women’s entrance into the professions and attributed this development to the availability of oral contraception beginning in the 1960s. Several years ago, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that 99 percent of U.S. women who have ever had sexual intercourse had used contraception at some point. So the recent controversial Hobby Lobby case no doubt appears somewhat surreal to many Americans who understandably have assumed that contraception—unlike abortion—is a settled, non-contentious issue in the United States.

To be sure, some conservatives, fearful of a female voter backlash in November, have tried to claim the case is about the religious freedom of certain corporations, and not contraception. But the case is about contraception. The majority in Hobby Lobby made this clear, claiming the decision only applies to contraception and not to other things that some religious groups might oppose, such as vaccinations and blood transfusions.

So why are Americans still fighting about something that elsewhere in the industrialized world is a taken for granted part of reproductive health care? As Jennifer Reich and I discuss in our forthcoming volume, Reproduction and Society, contraception has always had a volatile career in the United States, sometimes being used coercively by those in power, and at other times, like the present, being withheld from those who desperately need it.

The contraceptive wars started with the notorious campaign in the late 19th century of the Postmaster General Anthony Comstock, who successfully banned the spread of information about contraception under an obscenity statute. Margaret Sanger, who starting in the early 20th century, sought to bring birth control information and services to American women, was repeatedly arrested, before her eventual success in starting Planned Parenthood.

Gradually, after the Supreme Court cases mentioned above, the discovery and dissemination of the pill and steady increases in premarital sexuality, contraception became far more mainstreamed. Indeed, among its severest critics were feminist health activists of the 1970s, concerned about the safety of early versions of the pill and intrauterine devices (IUDs), as well as the use of “Third World women” as “guinea pigs” for testing methods. Federal and state governments became actively involved in the promotion of birth control: Title X of the Public Health Act of 1970 became the first federal program specifically designed to deliver family planning services to the poor and to teens. This legislation in turn drew angry protests from some activists within the African-American community who, pointing to the disproportionate location of newly funded clinics in their neighborhoods, raised accusations of “Black genocide.” (Title X exists to this day, albeit chronically underfunded and always threatened with being defunded entirely).

For a fairly short period after the Roe v. Wade decision in 1973, contraception was seen as “common ground” between politicians who were proponents and opponents of that decision. But as the religious right grew more prominent in American politics, contraception became increasingly attacked for enabling non-procreative sexual activity, as epitomized in the statement of the presidential candidate Rick Santorum, promising to eliminate all public funding for contraception if elected: “It’s not okay. It’s a license to do things in a sexual realm that is counter to how things are supposed to be.”

Moreover, many anti-abortionists have come to reframe some forms of contraception as “abortafacients.” Indeed, much of the Hobby Lobby case can be understood as a profound disagreement between abortion opponents and the medical community as to what constitutes an actual pregnancy and how particular contraceptives work. For the former, pregnancy begins the moment that sperm meets egg and fertilization takes place; for the latter it is the implantation of the fertilized egg in a woman’s uterus (the first point at which a pregnancy can actually be ascertained). The four contraceptive methods at issue in the Hobby Lobby case—two brands of emergency contraception and two models of IUDs—are deemed by many conservatives, including the plaintiffs in Hobby Lobby, to cause abortions, while the medical community has gone on record as saying these methods cannot be considered in this light, as they cannot interfere with an established pregnancy. According to medical researchers, these methods work by inhibiting ovulation, while one of the IUDs in question may prevent implantation in some circumstances.

Numerous other challenges to contraceptive coverage in Obamacare are expected to come before the Court, and some will seek employers’ right to deny all forms of contraception. What the outcomes of these cases will be and what success President Obama and Democrats will have in finding the “work-arounds” that they have pledged to pursue are not entirely clear at this moment. What is clear, however, is who suffers most from Hobby Lobby—not only the huge pool of women directly affected, but their families as well. Though we typically think of contraception as a “women’s issue,” in fact it plays a huge role in family well-being. A massive literature review by the Guttmacher Institute reveals the negative impacts on adult relationships, including depression and heightened conflict, when births are unplanned, and also shows the health benefits to children when births are spaced.

But the most effective contraceptive methods are the most expensive ones. As Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg noted in her scathing dissent, the upfront cost of an IUD can be a thousand dollars, nearly a month’s wages for a low-income worker. And many women who can’t afford an IUD apparently want one. One study has shown that when cost-sharing for contraceptive methods was eliminated for a population of California patients, IUD use increased by 137 percent. In light of this, my depressing conclusion about the Hobby Lobby case is that it follows a familiar pattern of American policies about contraception, and indeed of this country’s social policies more generally: The poorest Americans always seem to get the short end of the stick.