What If Everyone Involved in the Adria Richards Incident Was in a Union?

Unions help protect women, who are more likely to be harassed or retaliated against for making sexual harassment accusations, but also anyone who might have a colleague with a grudge.

Last week I wrote about the case of Adria Richards. Richards, who was developer evangelist at SendGrid, was fired after she publicly complained on Twitter about a dirty joke some male developers made at a conference; Richards’ complaint seemed to lead to one of those developers being firing. In the wake of the incident, Richards received an onslaught of racist, sexist, and threatening messages, while her now-former employer became the target of a serious denial of service attack and threats to its customers.

The situation is many kinds of messed up. But consider this alternate scenario: What if all the employees involved in this story had union representation in their workplaces? Most people think unions are all about salaries, and that’s part of what they do, but the idea that unions only focus on money comes mainly from anti-union politicians working to end collective bargaining rights.

Stripping the initial incident down to its barest facts, two men sat behind a woman and made a series of innuendo-laden jokes and remarks that she got tired of hearing. She complained about one of the jokes on Twitter. One of the men was fired. There was a public firestorm, and she was fired.

If they’d all had union representation, it’s possible that no one involved in this incident would have been fired, and we barely would have heard anything about it.

For one thing, most union contracts establish a grievance process that has to be followed before any covered employees are fired. This means you can only be fired for cause; your union will work to get your job back if your employer fires you without sufficient evidence of cause.

Criminal behavior and gross misconduct are obvious triggers for firing, but your union representative will still insist on proof of these violations, and not just unverified allegations. For lesser issues, there’s usually a requirement for a minimum number of warnings, with employees given the chance to correct their performance according to a set of guidelines negotiated with their boss and the support of their elected union representative, often referred to as a shop steward.

Let’s stipulate that it’s the exceptionally rare employee that a determined employer can’t find cause to fire if they really want to. After all, few of us are the paragons of diligent genius and productivity that we wish we were.

In the case of the two joke-cracking conference attendees, only one was fired, so it’s fair to assume that their employer didn’t consider the jokes an automatic firing offense. The likeliest scenarios are that the fired programmer had a history of trouble at work and this was just the last straw, or that his boss was itching for an excuse to send him packing because of a grudge, pressure from above to cut costs, or some other reason.

If both men had union representation and only one of them was fired, the public at large could probably rest comfortably in the belief that this incident was indeed the latest in a string of performance and/or behavior related problems—problems that the employee’s elected union representative would have had an active hand in trying to resolve. Without such representation, there’s no way to know.

In Richards’ case, it’s hard to imagine a union contract that would allow an employee to be fired for lodging a factual complaint. (No one has said that the remarks in question were inaccurately represented.) Such a complaint might not be actionable, and it might be made with the intention of preventing a recurrence of the problem rather than getting someone fired, but it wouldn’t be just cause for dismissal.

For women and minorities in general, union representation helps close the gender pay gap and increases access to health coverage, reducing structural discrimination in the workplace. That benefit is proportionally greater for minority women, who tend to face the most severe pay discrimination of any marginalized group. Even contractors’ unions organized on a guild model, which don’t tend to get involved directly in workplace disputes, can improve access to health coverage and help set pay scales that prevent exploitation.

When it comes to sexual harassment or hostile work environments, in a traditional shop-based union, elected union representatives work to establish facts, prevent retaliation, and make sure all parties are treated fairly. This protects women, who are more likely to be harassed or retaliated against for making accusations, but also anyone who might have a colleague with a grudge. Union representation, along with the grievance process, is the best way to ensure that all individuals, male and female, who are accused of harassment or hostile behavior have a chance for their side to be heard fairly—and, barring severe cases, have a chance to correct the behavior and keep their job.

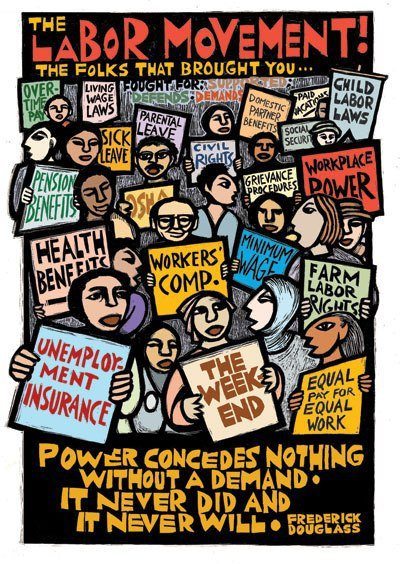

Which is why I’d suggest that anyone who’s worried about being fired for no good reason after reading the Adria Richards story should think about whether or not they could organize a union where they work. Reducing injustice, harassment, and discrimination in the workplace is a big part of what unions were invented for.