Justice in Colorado Will Not Come From Putting More Pregnant Women in Danger

The attack on Michelle Wilkins was an unfathomable act of cruelty. However, Colorado legislators must not use it as grounds for passing new feticide laws that will actually make pregnant women vulnerable to arrest and punishment.

Last month, Michelle Wilkins was the victim of a horrific crime; she was beaten and stabbed, and the baby she was expecting to give birth to was cut from her belly. Miraculously, Wilkins, who had been 34 weeks pregnant, survived the physical assault. This was an unfathomable act of cruelty. However, justice will not be achieved by Colorado legislators using it as grounds for passing new feticide laws that will actually make pregnant women vulnerable to arrest and punishment.

Dynel Lane, the woman accused of attacking Wilkins, has been charged with numerous crimes, including the attempted murder of Wilkins and first-degree unlawful termination of a pregnancy under Colorado’s Crimes Against Pregnant Women Act. The Colorado legislature carefully crafted this law in 2013 to respond to attacks on pregnant women, and to recognize and punish violence against them that causes a pregnancy loss. If Lane is convicted of these charges, she could be sentenced to more than 100 years in prison.

According to the Catholic Archbishop in Denver and some Colorado legislators, this is not enough. They believe that the perpetrator should also be charged with the crime of fetal murder. So far, Colorado lawmakers have wisely refrained from passing a feticide law prosecuting people who cause the death of a fetus, embryo, or fertilized egg, instead keeping the focus on pregnant women. Similarly, Colorado voters have repeatedly rejected attempts to amend the state’s murder laws through so-called personhood measures that would have changed the definition of “child and persons” in every criminal law in Colorado to include fertilized eggs, embryos, or fetuses. In other words, Colorado has refused to pass laws that are being used to punish pregnant women—and it should continue to do so.

Thirty-eight states have feticide laws. Virtually all of them were passed in the wake of shocking acts of violence against pregnant women and with the promise that they would protect pregnant women and their “unborn children” from harm. Yet not a shred of evidence exists to show that these laws have reduced violence against pregnant women. Instead, there is hard evidence that they actually hurt them.

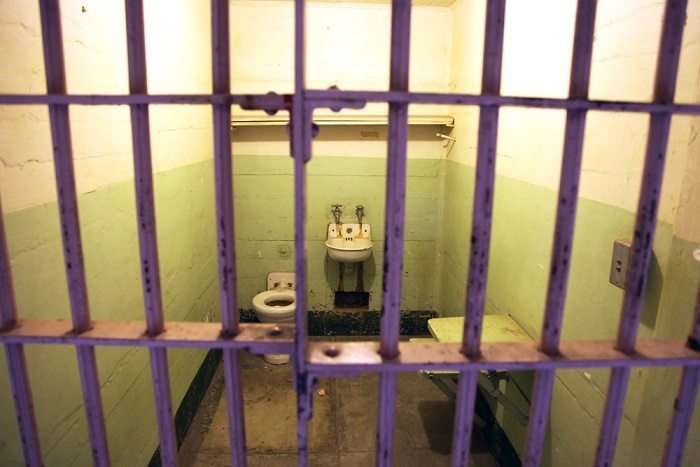

There are numerous cases in which these laws have been used—not to protect pregnant women, but to lock them up.

Women in California, Georgia, Tennessee, South Carolina, and Utah who suffered stillbirths or delivered babies who died shortly after birth have been charged directly under state feticide laws. In Utah, for example, a feticide law was used as the basis for arresting and charging a woman who gave birth to twins, one of whom was stillborn. This mother was arrested on charges of criminal homicide—a first-degree felony—based on the claim that she had caused the stillbirth by refusing to have cesarean surgery two weeks earlier. A spokesperson for the Salt Lake County district attorney’s office explained that the decision to charge her with homicide was, according to the New York Times, “required by Utah’s feticide law, which was amended in 2002 to protect the fetus from the moment of conception.” Facing a storm of controversy, Utah prosecutors eventually dropped the murder charge. After spending 105 days in jail, the mother pleaded guilty to two counts of third-degree felony child endangerment as part of a plea bargain that allowed her immediate release from jail.

In Iowa, a woman who fell down a flight of stairs while pregnant and then went to the hospital was arrested for the crime of attempted feticide. She was held in jail for two days before a national uproar led to her release—though police claimed that they would have kept her locked up if she had been in her third trimester of pregnancy at the time of the fall. In Indiana, a pregnant woman who attempted suicide while pregnant was held in jail for more than a year on a charge of attempted feticide. Another Indiana woman, Purvi Patel, was convicted of feticide based on the claim that she had attempted to terminate her own pregnancy. Just this week, she was sentenced to 20 years in prison.

Even when women are not charged directly under feticide laws, such legislation is often used to support the interpretation of generally worded murder statutes, child endangerment laws, reckless driving laws, drug delivery laws, and others to permit the arrest and prosecution of women who have experienced pregnancy losses. In South Carolina, for example, the state’s feticide law (created in response to a brutal attack on a pregnant woman) became the basis for making the state’s child endangerment law applicable to pregnant women. As a result, women who have used cocaine and given birth to perfectly healthy babies, as well as women who became pregnant and used marijuana or alcohol, pregnant women who attempted suicide, and women who have experienced stillbirths, have all been subject to arrest and prosecution. And when these laws have been used to justify punishment of pregnant women, low-income women and women of color have been disproportionately targeted for such arrests and prosecutions.

We must not let the terrible tragedy in Colorado be used to further a political agenda that is actually dangerous to women. Instead, we should find ways to support Wilkins and her family, while acknowledging our collective grief and horror and the need to end violence against pregnant women.