Flint Investigator: Officials Could Face Manslaughter Charges in Water Crisis

Todd Flood, a special counsel leading the probe into Flint’s water contamination emergency, told the press that his team is taking the case “very seriously.”

Officials involved in the Flint, Michigan, water crisis may face charges as serious as manslaughter if they are found guilty of a “breach of duty” or “gross negligence,” a top investigator revealed Tuesday.

Todd Flood, a special counsel selected by the office of Michigan Attorney General Bill Schuette to lead the probe into Flint’s water contamination emergency, told the press that his team is taking the case “very seriously.”

“We’re here to investigate what possible crimes there are, anything [from] involuntary manslaughter or death that may have happened to some young person or old person because of this poisoning, to misconduct in office,” Flood said, according to the Washington Post.

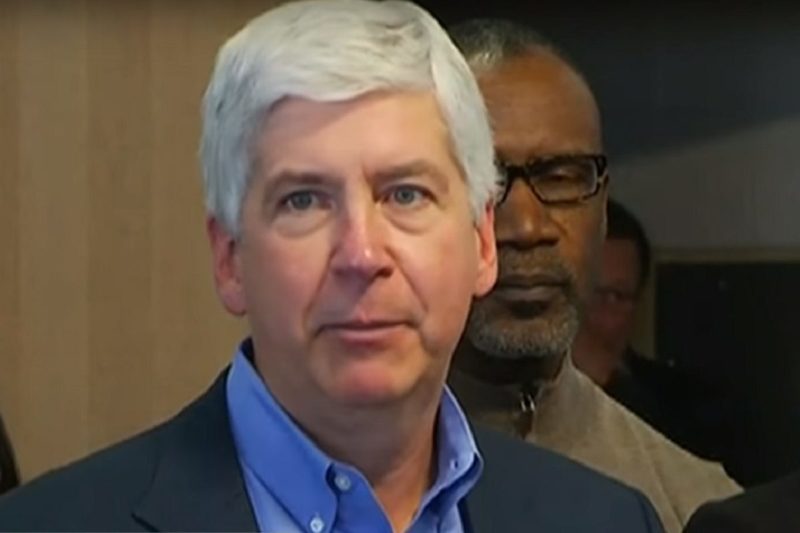

Flood was tasked with examining both civil and criminal liability in the ongoing disaster since Schuette’s office has its hands full defending Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder (R) and various state agencies in a slew of lawsuits brought by Flint residents. They say that city, state, and county officials ignored concerns over lead contamination in the drinking water supply for more than a year.

A congressional hearing last week set the stage for the investigation by hauling several officials in for questioning, including Keith Creagh, a political appointee who oversaw the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality (MDEQ) throughout the crisis, and Joel Beauvais, deputy assistant administrator for the Environmental Protection Agency’s (EPA) Office of Water.

Both faced questioning by members of the U.S. House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform, which convened the hearing. Congresswoman Sheila Jackson Lee (D-TX) evoked a cult leader’s 1978 mass murder-suicide of nearly 1,000 of his followers, stating, “There is a Jim Jones in Michigan, who gave a poisoned concoction to children and their families.”

Flint switched its water source from Lake Huron via the Detroit Water and Sewage Department to the Flint River in April 2014 under the guidance of emergency managers appointed by Snyder. Many of the city’s 100,000 residents quickly noticed changes in their household water, from foul odors to severe discoloration, a result of the corrosive Flint River water eating away at old lead pipes.

People began to fall ill, with children breaking out in rashes and adults losing clumps of their hair in the shower. While these symptoms have now been widely recognized as signs of lead exposure, officials insisted for months that the water was safe to drink. Leaked documents and emails dating back to 2014 reveal that numerous departments, including the EPA and the MDEQ, were aware of the problem for several months and took steps to safeguard their employees against lead poisoning while Flint residents—who are mostly poor and predominantly Black—were forced to drink, cook, and bathe with the toxic water.

The most recent twist in the saga involving officials’ handling of the contamination came on Tuesday, when the Detroit Free Press published a cache of emails secured through a Freedom of Information Act request revealing that the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) warned that bureaucratic hurdles were standing in the way of an efficient response to an outbreak of Legionnaires’ disease following the switch to the Flint River—eight months before Snyder spoke publicly about the illness.

The governor and his administration have maintained for more than a month that there is insufficient evidence to prove a link between the potentially fatal bacterial infection and Flint’s lead-poisoned water, but the latest email dump could make it hard for officials to stand by this statement.

In an email dated April 27, 2015, a CDC employee told Genesee County health officials that the outbreak of Legionnaires’ was “one of the largest we know of in the past decade, and community-wide, and in our opinion and experience it needs a comprehensive investigation.”

The CDC official went on: “I know you’ve run into issues getting information you’ve requested from the city water authority and the MI Dept of Environmental Quality … Not knowing the full extent of your investigation it’s difficult to make recommendations … from afar.”

There have been 87 reported cases of Legionnaires’ disease in Genesee County, and nine confirmed fatalities. The outbreak added to a long list of pressing health concerns for Flint residents following the water supply switch in 2014, including the risk of miscarriage and pre-term delivery for pregnant people, and permanent brain damage and reduced cognitive functioning in young children.

Investigators made no mention of the CDC correspondence in Tuesday’s press conference in Lansing. Flood assured reporters that he would lead a “full and comprehensive investigation” into the many aspects of the disaster.

Several state legislators, including Senate Majority Leader Arlan Meekhof (R-West Olive), have raised a red flag over the cost of the inquiry, referencing Flood’s hourly rate of $400. Others have expressed concerns over Flood’s impartiality given that he has made political contributions to both Snyder and Schuette, according to the Detroit Free Press.

The team is comprised of nine full-time investigators. It includes former Detroit police officers, and the former head of Detroit’s FBI office, Andrew Arena, who claims he came out of retirement because the mass poisoning of Flint’s residents is the “the biggest case in the history of the state.”

A large crowd gathered Wednesday morning at the state capitol, where Snyder was slated to unveil his proposed annual budget. Protesters booed and called for the governor’s resignation, according to local news reports.

Snyder vowed to increase spending on Flint by $195 million, bringing the total pledged to the crisis to $232 million. Snyder earmarked $37 million for safe drinking water and dedicated $63 million toward the elusive goal of “physical, social, and educational well-being,” as well as $50 million toward water bill relief.

The budget did not allocate funds for the immediate removal and replacement of Flint’s aging pipes, which are continuing to leach lead into the water supply. Flint Mayor Karen Weaver said last week that replacing the pipes, particularly in the homes of pregnant women and families with children younger than 6 years of age, was her “top priority.”