Now Is the Time to Push Iran on Women’s Rights

The world’s governments looking to build stronger ties with Iran must redouble their efforts to hold Iran’s leaders accountable for advancing women’s issues in the wake of the nuclear deal, not excuse them.

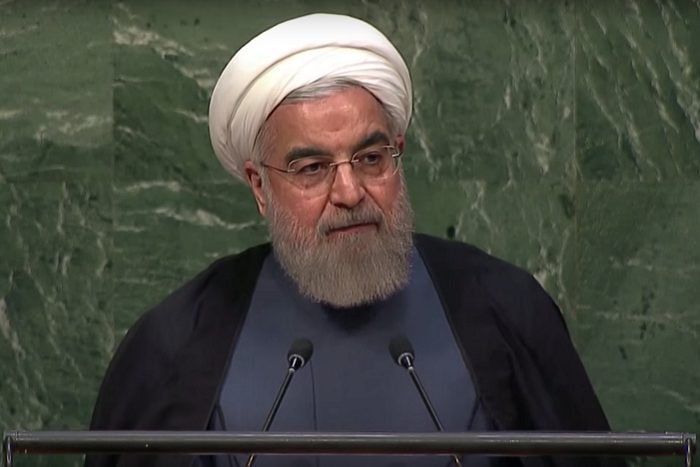

Last week, Iranian President Hassan Rouhani addressed the United Nations General Assembly, touting Iran’s revamped efforts, born out of the recently signed multilateral nuclear agreement, to become a more cooperative and full member of the international community.

His speech focused on the nuclear deal and his positive outlook toward improved relations with the United States. But for 35 million Iranian women, absent from Mr. Rouhani’s remarks was an explanation of how he intends to keep his promise to ensure women are treated as full members of the country he represents. The world’s governments looking to build stronger ties with Iran must redouble their efforts to hold Iran’s leaders accountable for advancing women’s issues in the wake of the nuclear deal, not excuse them.

In September, Niloufar Ardalan, the captain of Iran’s female indoor soccer team, was prevented from traveling to compete in a tournament in Malaysia. Her husband, sports journalist Mahdi Toutounchi, refused to let her renew her passport to ensure she was in the country to accompany their son to his first day of school, which is, shockingly unjust yet perfectly legal in Iran. Indeed, an Iranian woman cannot leave the country without her husband’s consent, a law that stretches back to before the 1979 revolution. Ardalan’s case is particularly tragic, though, because she represents an athlete capable of competing at the highest level who is unable to pursue her talents and represent her nation abroad because of arcane, restrictive legal norms. In a touching act of solidarity, Ardalan’s teammates began chanting her name as she greeted them in the airport upon their return home from winning the tournament.

The fact remains, how are we to believe that Iran is “looking to the future … with a bright outlook for cooperation and coexistence,” as Mr. Rouhani conveyed at the UN General Assembly, when its laws would require leaders such as German Chancellor Angela Merkel to ask for permission from her husband before attending the United Nations General Assembly?

These norms are not only discriminatory, but out of touch with the reality of Iranian women, who are among the most educated women in the region. Literacy and primary school enrollment rates for women and girls are estimated at more than 99 percent and 100 percent, respectively, and gender disparity in secondary and tertiary education is effectively nonexistent. But no matter how educated a woman in Iran is, all deserve to enjoy the same rights as Iranian men.

Advancements in education and social advancement have not been matched by equivalent advancements in the legal status of women. Women’s employment rates are half that of men at every level of educational attainment. Iran ranks near the bottom (137th out of 142 countries) for political empowerment of women, meaning the presence of women in top elected and appointed roles, according to the World Economic Forum’s 2014 Gender Gap Index.

These disparities, while having some social and cultural roots, are reinforced by design.

Iranian law requires women to seek their husbands’ permission to travel, work, and attend university. And when a husband is abusive, women face huge legal hurdles in getting a divorce. Perversely, in the eyes of the law, adult women are not capable of making these important life decisions, yet girls can legally marry starting at 13 years old and are treated as “adults” when it comes to criminal responsibility starting at age 9.

It seems some leaders in Iran want to double down on this systematic gender discrimination. They propose laws that would require businesses to hire men over women, and married people over unmarried people. Some government offices have already restricted the hiring of women. What’s more, in some state universities, women have been barred from certain majors. Iran produced Maryam Mirzakhani, who last year became the first woman to win the Fields Medal, the top international prize in mathematics. Still, it’s unacceptable that some institutions still prohibit Iranian women from pursuing engineering and math.

Of course, Iranian women, and many men, have not silently accepted these oppressive laws. For example, the Facebook campaign My Stealthy Freedom, which promotes women’s freedom of expression by sharing photos of Iranian women choosing not to wear their hijabs, has gained almost 900,000 likes since its 2014 launch. Iranians have been trying to change such repressive laws for decades, but those who attempt to do so often pay a heavy price. At least 50 women human rights defenders are currently in prison as a result of their advocacy efforts.

Thirty-four-year-old Bahareh Hedayat has been in prison for six years for her activism. Hedayat is a founding member of the “One Million Signatures” campaign, a grassroots movement demanding changes to discriminatory laws. And just when she was due to be released, judicial authorities decided to illegally reinstate an expired probationary sentence, tacking on two years to her prison term. [Full disclosure: I am a member of the campaign.]

Within government, Iran’s vice president for women and family affairs, Shahindokht Molaverdi, seems genuinely concerned about the situation. She recently issued a harsh criticism of bans on women attending live sporting events. But Molaverdi has little institutional power. If her efforts and those of the women’s rights movement are to be successful, they will need the strong backing from voices inside and outside of Iran.

Starting with Rouhani, we all must fight harder to create the space to criticize discriminatory policies. Iranian women are too educated, talented, and ambitious to remain held back by an archaic set of rules. To truly become a legitimate actor in the world, Rouhani must now prioritize the rights of women—and the international community must demand reform.

The reform and modernization of Iranian law with regard to expanding human rights and ensuring gender equality would release the limitless potential of the Iranian people, and especially Iranian women. But if the Islamic Republic keeps the gates closed, women will not be passive. They will continue to educate the masses to peacefully resist discrimination. We believe that justice and equality can best be achieved through patience and tolerance.