Percy Sutton’s 1966 Abortion Rights Bill: Groundbreaking, But Often Unremembered

Though many remember New York's Percy Sutton as an investor, lawyer, and power broker, he also introduced the state's first bill that would have relaxed abortion restrictions—opening the door for the liberalization of New York's abortion laws before Roe v. Wade.

This piece is published in collaboration with Echoing Ida, a Forward Together project.

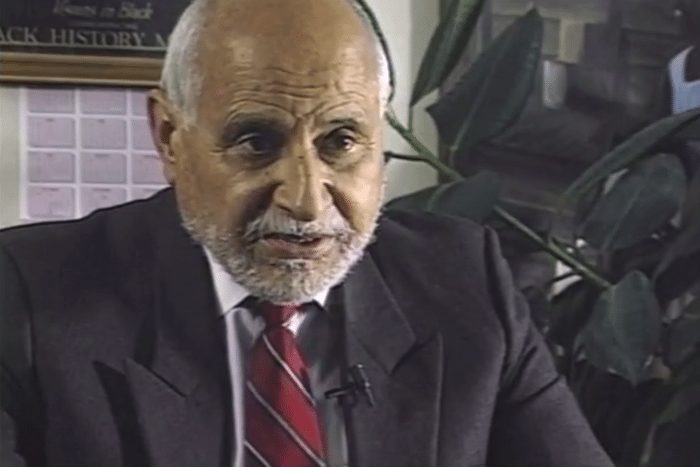

By the time of his death in 2009, New York’s Percy Sutton had long earned his reputation as a pioneer and power broker. Many New Yorkers still remember him as an investor in the famed Apollo Theater and WLIB-AM, New York’s first Black-owned radio station. Others knew him as one of the Gang of Four, a quartet of Black male movers and shakers who left indelible marks on the Empire State. A lawyer and consummate negotiator, Sutton could do heavyweight horse-trading with a smile and a debonair suit.

But Sutton used his skill and experience in a lesser-known way to make history too: In 1966, during his brief time as a member of the New York assembly, he introduced the state’s first bill that would have legalized abortion in cases of rape, incest, or danger to the pregnant woman’s health. At the time, New York’s 80-year-old law prohibited all abortions, except to preserve the life of the pregnant woman. As Sutton himself recounted in the documentary From Danger to Dignity: The Fight for Safe Abortion, an old military buddy “had come back home after World War II, only to have, within the first year of his return, his wife die as a result of a botched abortion. This background demanded that I take some action when I had the opportunity.” Twenty years later, Sutton responded with the bill. Although his proposal was quickly squashed, Sutton, along with local feminists, doctors, sympathetic clergy, and activist attorneys, had paved the way for the 1970 liberalization of New York’s abortion law.

Sutton’s power—and, perhaps, why he was able to take a risk in introducing abortion reform—lay largely in his broad range of contacts and influence. He made strategic alliances with Republicans, thereby gaining more committee posts and influence for Black Democratic legislators. And Sutton’s strong base in Harlem, where he had practiced law since the early 1950s (and worked nights as a subway operator as a young attorney), made him a force to be reckoned with even when he wasn’t holding office. He and his Gang of Four compadres—current Rep. Charles Rangel, New York’s first Black mayor David Dinkins, and New York’s first Black secretary of state Basil Paterson—dominated the politics of Black New York for decades. He crossed the aisle within the Black community too, balancing work with the NAACP while also representing Freedom Riders; when Malcolm X was shot to death 50 years ago this month, it was Sutton who pounded the pavement and found a funeral home that would bury the slain Black nationalist when most refused.

So it was fitting that when Sutton decided to take on abortion reform, he took the issue to the proverbial street. A few months before he introduced his bill, he penned editorials in the New York Amsterdam News—one of the nation’s most influential Black newspapers and itself later part-owned by Sutton—to make his case to his constituents.

In his five-column series titled “Is Abortion Ever Right?” Sutton addressed ethical, moral, and medical arguments for and against abortion and debunked faulty conventional wisdom. He interviewed doctors who said that unsafe abortion was a leading cause of maternal deaths and that “contrary to popular belief, most abortion deaths occur not among teenagers, but among married housewives who already have three or more children.” And as religious opposition to abortion mounted, Sutton noted that many Catholics supported medically necessary abortions for ectopic pregnancies, though he also said some Catholic doctors had argued that “there are few, if any instances where abortion is medically indicated.”

By contrast, “Dr. D,” a Harlem physician featured in the February 19, 1966 column, told Sutton “don’t be ridiculous” when Sutton asked him whether abortion was ever right. The doctor explained that he supported abortion in cases of rape and incest—which Sutton’s reform bill would have allowed. Sutton even interviewed Dr. D’s own pastor, who echoed the sentiment, adding that he believed “in some cases, THE FAILURE TO ABORT IS WRONG!”

Judging by later installments of the column, Sutton’s abortion advocacy apparently riled some readers. It’s not clear how much pushback Sutton encountered or whether more readers agreed with his position than not. But in the fourth article, Sutton opened with: “Hold on, Amsterdam News readers! I am not an abortionist. I’m an attorney and an Assemblyman. Cut off your telephone calls and stop the letters of protest. The fact is, I am opposed to abortions, except under very strict, hygienic hospital conditions.” Sutton would later say in From Danger to Dignity that some Black ministers who supported him on other issues threatened to pull their support from him in any future elections due to his abortion stance.

But unlike other Black legislators whose abortion-reform efforts factored in their subsequent political defeats—such as Tennessee state Rep. Dorothy Brown and U.S. Sen. Edward Brooke (R-MA)—Sutton’s work on reproductive rights didn’t jeopardize his career. In 1966, months after his failed abortion bill, Sutton became borough president of Manhattan. It wasn’t quite the crown jewel of New York politics (Sutton would later run for the mayorship and lose), but it was close.

As his political and entrepreneurial fortunes rose, Sutton remained attentive to the issue of abortion access for poor, mostly Black and Latina women in New York. In 1969, he supported picketing hospitals nationwide to demand that they abolish physicians’ therapeutic abortion committees. These groups of gatekeeping doctors decided when they could provide an abortion before Roe. As Sutton knew, getting these doctors to approve women’s requests often required preexisting relationships with a physician; multiple and costly visits (sometimes to a psychiatrist who could vouch for a woman’s pregnancy-related distress); and navigating bureaucracy. Altogether, these factors meant that Black and Puerto Rican women had less chance of accessing legal abortions at public hospitals than privileged women, who could pay for private and regular health care.

Interviewed by the New York Post about the protest, Sutton was undaunted by repeated failed efforts to change the abortion law. He insisted that “abortion should be had at will. It should only be a matter between a woman and her doctor. The state should not be a party to it”—a seeming departure from his “I am not for abortion” statement in the Amsterdam News four years prior.

By 1970, Sutton had helped to bring that vision one step closer to reality. After his legislative stint had ended, he still served on a public-health panel that held public meetings that became popularly known as “Sutton’s hearings.” At first, these hearings were markedly male-dominated. Then, in a 1969 panel, women activists crashed the meeting, literally adding their voices to the mix. They demanded a full repeal of the abortion ban, screamed “Free abortions!” and complained that the only woman among more than a dozen speakers was a nun.

For the protesters, incremental reform—like that initially proposed by Sutton—was not an option. Sutton and the other panelists heeded their requests to be heard: By yet another batch of hearings in March 1970, women had been added to the slate of speakers, testifying about the toll that unsafe abortion, unplanned pregnancy, and lack of contraceptive access did to their lives. Within months—and in a vote that had one New York state legislator crying in conflicted frustration and fear of what his family might think—the state assembly voted to allow abortions up to 24 weeks if performed by a doctor.

Sutton’s original 1966 legislation, while much less sweeping than the one New York ultimately passed, had eased open the door for reproductive rights reform. Four years later, abortion-rights activists were continuing down the path Percy Sutton had forged with a friend’s decades-old abortion story and one unsuccessful bill.