For Immigrants After Obama’s Executive Order, Mix of Joy, Sorrow, Determination

Dozens of immigrants and activists gathered at the Washington, D.C., offices of United We Dream on Thursday to hear what President Obama would say to the nation about their families and their community.

Read more of our coverage about the Obama administration and immigration reform here.

Dozens of immigrants and activists gathered at the Washington, D.C., offices of United We Dream on Thursday to hear what President Obama would say to the nation about their families and their community.

They already had some sense of what they would hear; the details of the plan had been released to advocates ahead of time.

They knew that Obama’s new executive order will give nearly five million immigrants a three-year reprieve from the daily fear of being deported and torn from their families.

They knew that those five million people would be able to apply for work permits and even get driver’s licenses, although they still wouldn’t qualify for the affordable health-care access that would lift more of them out of poverty and help their mothers care for their families.

They also knew that only some of their mothers, sisters, neighbors, and friends would be safe.

They had already made some emotional phone calls to people they knew: Good news, the president is going to announce something today that will change your life. Or, too often, I’m so sorry. We hoped for better, but your father won’t qualify after all.

Most of the newly protected immigrants, about four million, are the parents of U.S. citizens or green card holders.

Another 270,000 are so-called DREAMers who came to this country as children. The president will expand his Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program to people who are now over 30 and who came to the country between 2007 and 2010, but the cutoff age for having first crossed the border is still 16.

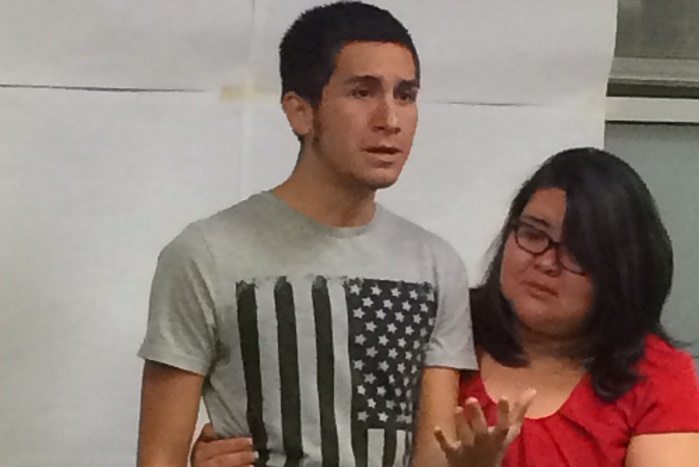

Those technical changes mean everything for Juan Carlos Ramos. He crossed the border with his brother in 2008, too late to qualify for DACA when it first came out in 2012.

He still volunteered to help sign people up as soon as he heard that the program existed, six days after his high school graduation. His activism meant constant painful small talk about whether he had applied for the program himself yet, but he was determined to help others achieve what he couldn’t.

Ramos, who was 15 when he came to the United States, now can finally sign up for the program himself. But his brother can’t; he was already 16 on the day they crossed the border.

Their parents can’t get relief either. Advocates had pushed hard for the parents of DREAMers to be included in the president’s action, but they didn’t make the cut.

The speech itself was more powerful and empathetic than some had expected. There was the usual boilerplate about people who break the laws needing to pay their taxes and get to the back of the line—a frustrating line of argument for many taxpaying undocumented immigrants who have had years-long bureaucratic headaches trying to apply for citizenship.

But Obama also made a strong moral case for doing what he can to help immigrants as long as Congress won’t. He appealed to scripture in saying, “My fellow Americans, we are and always will be a nation of immigrants. We were strangers once too.” He challenged America to be a nation that values families, not one that “accepts the cruelty of ripping children from their parents’ arms.” He called for deporting “felons, not families; criminals, not children.”

It was a deeply affecting speech, Felipe Sousa-Rodriguez told Rewire. The part that really touched him, he said, was “when the president acknowledged that we exist. When the president acknowledged that we contribute. When the president said that our families should not be ripped apart, that we deserve dignity, that we deserve to stay in this country.”

After the speech concluded, the United We Dream watch party attendees put their arms around each other’s shoulders and erupted into a familiar chant from their days protesting in the streets or holding sit-ins in congressional offices.

I am! Somebody! And I deserve! Full equality! Right here! Right now!

But more of the aftermath was near-silence, punctuated by sniffles around the room as people wept, comforted each other, and listened to people tell their stories.

They talked about the fears they could now be free of, the fears they were still burdened by, the dreams they may never realize or the dreams they could finally pursue.

Ramos collapsed into tears talking about his parents, and the room filled with supportive snaps while he tried to regain his composure and a friend came up to comfort him.

“They have always been there for me,” he said finally. “And I know that I will continue fighting for them and for my brother, whoever needs it, no matter who we have to talk to, if I have to stay up late doing whatever work we need to do, but we’re going to do it.”

He also dreams of becoming an architect one day and building his parents’ house, he told Rewire.

Beatriz Perez, a mother of four, told the crowd in Spanish how much she celebrated in 2012 when her two undocumented children qualified for deportation relief under DACA.

Now she has even more reason to celebrate; her other children are citizens, so now she can come out of the shadows.

“Thank God that it affects me, because I’ve been here for 21 years without being able to get a driver’s license or being able to walk down the street without being afraid,” she said.

It didn’t dawn on Elena Calderon at first that the new order meant her undocumented father was safe. She’s a DACA recipient and the youngest of five, and she actually forgot that her older brother had managed to become a citizen.

One of Calderon’s earliest memories is of her father carrying her across the border as a 3-year-old because she was too small to run, of crouching to hide from the border patrol while her mother held rosary beads and prayed.

Her father was the only member of her immediate family not to qualify for protection through legal status or DACA; now, finally, all his risk and sacrifice would mean something for him too.

Still, Calderon can’t stop thinking about the families who aren’t as fortunate as hers. “You want to celebrate, but at the same time you can’t stop thinking about everyone else who is being left out,” she said.

Emotions were both high and profoundly mixed in the room for this reason. Everyone had worked hard, everyone had struggled, everyone had seen the harms that the country’s broken immigration system had visited on their community. Only some of them would benefit personally.

But those who grieved for themselves or their families refused to let that grief overtake the joy of those who would finally be protected. They couldn’t. They had worked too hard, for the entire community and not just for themselves, and they knew there was still plenty of fight ahead.

Ray Jose, a 24-year-old undocumented immigrant and DACA recipient from the Philippines, has spent a lot of time away from his family over the last year or two because of his work with United We Dream. He told Rewire that the executive order is a bittersweet victory for him since his parents still won’t qualify.

But the whole reason Jose’s family came to the United States, he said, was to help him and his sister pursue their dreams. He thought his dream would come through a college education, but campus activism with other undocumented youth set him on an unexpected path.

“My dad told me, ‘God has plans.’ And although he’s not included in this one right now, that he’s proud of me. He’s happy that I’m doing this work, because it’s what I’m meant to do,” Jose said.