Loving Day, Juneteenth, and the Right to Family

The anniversary of the Loving case on June 12 and Juneteenth on the 19th should remind us that, within the African American freedom struggle and broader movements for equality, there has always been a struggle to determine the right to marry, select an intimate partner of one’s choice, and to form the families that we want.

This piece is published in collaboration with Echoing Ida, a Forward Together project.

In June, I celebrate two commemorations that may not make it onto standard calendars of holidays and observances: Loving Day on the 12th and Juneteenth on the 19th.

Each of these days should remind us that, within the African-American freedom struggle and broader movements for equality, there has always been a struggle to determine the right to marry, select an intimate partner of one’s choice, and to form the families that we want.

On June 12, 1967, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Loving v. Virginia that Virginia’s Racial Integrity Act, a 1924 law that banned marriages between whites and “coloreds,” was unconstitutional. That law made illegal all formalized unions between whites and non-whites, including Blacks and American Indians. Blatantly eugenic in nature, the act aimed to maintain the purity of whites and accomplish the impossible and retroactive task of “genetic segregation” of populations that had been intermingling since Jamestown and the arrival of the first Africans to the shores of what would become Virginia, in 1619.

Almost a century earlier, on June 19, 1865, Union troops arrived in Galveston, Texas, bearing news that the Emancipation Proclamation had ended slavery in the rebelling territories more than two years prior. Though there are multiple stories about why such important news hadn’t trickled down to the enslaved people there, a Union General read a decree that there was to be “absolute equality of personal rights and rights of property between former masters and slaves.” (Well, not really: The rest of the executive order came with the warning that the freed people were expected to remain quiet and at the places where they were enslaved, to work for wages and for the very people who had just owned them, and would not be “supported in idleness”—setting up a labor system stacked against them and to the benefit of literate ex-masters with few scruples about using violence.)

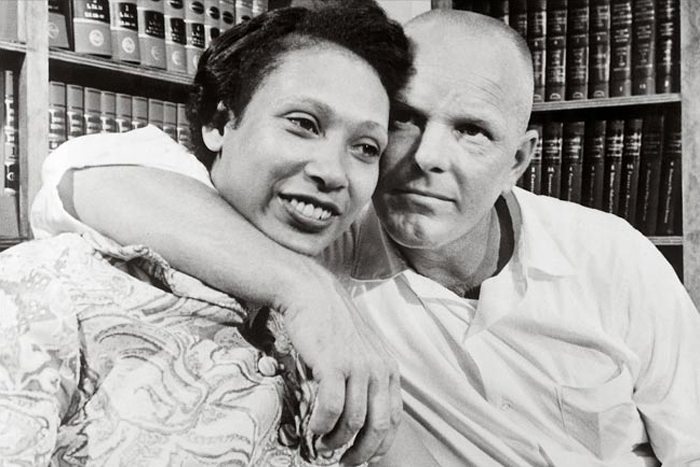

So what does Juneteenth have to do with Loving Day? In the Loving case, Mildred Jeter, a woman of mixed Black-white-Indian ancestry, and her white partner, Richard Loving, had married secretly in Washington, D.C., in the late 1950s.

Mildred, 18 and pregnant with the couple’s first child, and Richard knew they were violating the law in their home state, and Richard snuck into their house under the cover of dark. A tip alerted police that the Lovings were in the house, and during a nighttime raid in which officers hoped to catch the couple in flagrante, the Lovings showed their marriage certificate.

Under the law, their union was null and void, and no marital rights accrued to them. Their children were considered “illegitimate” and also living evidence that the couple had crossed racial boundaries the law was meant to reinforce. Mildred and Richard Loving were sentenced to a year in jail. A local judge offered to suspend the jail time if the couple agreed to leave the state.

The Lovings lived in a world that slavery and its offspring, segregation, had made. When Galveston’s enslaved people danced in the streets upon learning of their freedom in 1865, that freedom came with some marriage rights but not others. The enslaved hadn’t been able to seek a legal marriage; after all, property could not make binding decisions or marry other property. After freedom, marriages that began under slavery became recognized under law. But not all marriages were legal. Citizens of the post-Civil War world were in the midst of a massive social, economic, and legal shakeup. In states nationwide, legislatures debated whether their state constitutions would allow “social equality”—code for interracial marriage. Allowing interracial marriage would change the political landscape and, literally, the complexion of this newly unified nation. Some states seesawed between permitting interracial marriages; South Carolina’s 1868 constitution was mute on interracial marriage, but its 1895 version banned them explicitly.

Politicians and pundits also knew that interracial relationships were nothing new; states that banned Black-white marriage often failed to ban nonmarital interracial sexuality—likely an intentional loophole.

The Lovings’ own state, Virginia, began passing laws against interracial relationships between enslaved people and whites in the late 1600s because such contact inevitably produced a mixed-race population of uncertain status. As historian Martha Hodes has written, interracial marriages and unions occurred from the early colonial period to the 19th century in places like Maryland’s Eastern Shore, where white women indentured servants literally gave up their freedom due to relationships with Black enslaved men.

That’s not to say that, particularly in the post-Civil War South, interracial relationships, much less marriage, was always met with approval. Before local police busted in on the Lovings, Black-white couples were routinely charged with fornication and heavily fined in local courts nationwide. Particularly unlucky interracial families got unwelcome visits from the Ku Klux Klan or other groups of violent white supremacists. A September 1885 New York Times article recounted the persecution of the Davis family of Fairfield County, South Carolina; Tom Davis, a prominent white landowner worth $45,000, left his property and his biracial family for Mississippi when vigilantes intent on stamping out “miscegenation” attacked his homestead.

Nor is it to say that the tangled issue of interracial marriage applied only to Blacks and whites. Western states frequently disallowed marriages between Asians and whites. In 1948, one of the important precedents for Loving came from the Supreme Court of California, affirming a marriage between a Mexican-American woman (classified as white) and a Black man. In that case, Perez v. Sharp, the justices upheld that marriage is a fundamental right that cannot be circumscribed by racial prejudice.

So on Loving Day, I take the name of the landmark case as an exhortation to be more loving and to uphold the couple’s legacy of fighting for the right to partner with whom and when we all choose.