Justice Kennedy and the Supreme Court’s Tilted Scale

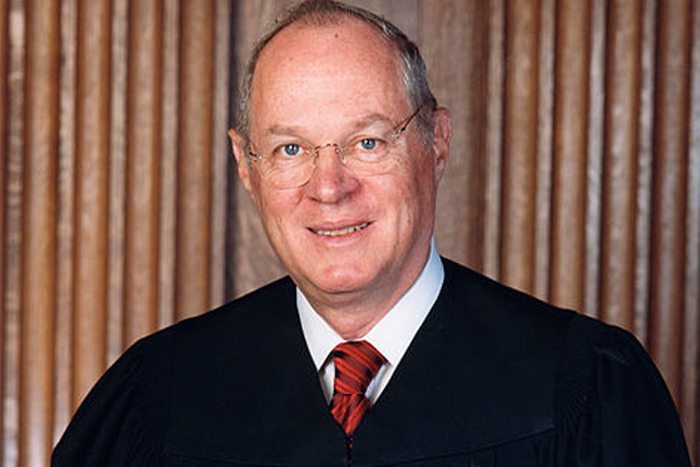

In a recent ruling by the Supreme Court, which paved the way for similar state-level legislation, five justices voted in favor of weakening the separation of church and state; but the implications of Justice Anthony Kennedy’s libertarian jurisprudence are the most dangerous and far-reaching.

The text of Mississippi’s recently passed law, SB 2681 or the Religious Freedom Restoration Act, lavishes careful procedural and heraldic language on a proposed change to the state seal, adding “In God We Trust” to it. It does make for interesting reading, summoning the stilled bones of antiquated language into a peculiarly modern shape—for all the conservative chest-beating about a grand restoration of traditional “Christian America,” Mississippi’s bill had to note that it was changing a seal that had existed unchanged since 1818. So much for tradition.

But the symbolism matters. This legislative blazonry was, after all, appended to a successful anti-LGBT “religious freedom” bill, not dissimilar from the sort that has been making the rounds lately. SB 2681 provides that “government shall not substantially burden a person’s exercise of religion,” with broad enough language to suggest that this empowers private business owners to discriminate; it’s what I’ve called the “crowdsourcing of bigotry.”

This is primarily a state-level phenomenon, but a recent ruling by the Supreme Court in Town of Greece v. Galloway gives stark insight into the legal thinking that made SB 2681 what it is. That ruling allows government-sponsored religious invocations to be more explicitly sectarian, paving the way for mass, explicitly religious prayer in legislative sessions—and quite possibly other publicly sponsored events. The ruling is potentially far-reaching, dramatically eroding the power of courts to enforce the Establishment Clause.

One Roanoke, Virginia, supervisor—Al Bedrosian—already wants to ban all other faiths from any public invocations at legislative sessions in the city (he’s terribly concerned about Wiccans and Satanists, apparently).

In light of that, it is instructive to consider Justice Anthony Kennedy’s majority opinion in Town of Greece, and how it is that his seemingly measured and unobtrusive vision of government power has actually empowered people like that hapless supervisor to use a particularly perverse reading of religious freedom to deny minorities full citizenship. Five justices voted in favor of weakening the separation of church and state, but the implications of Kennedy’s libertarian jurisprudence are the most dangerous and far-reaching, and his profoundly naive view of power is one that is creating one of the biggest juridical obstacles to women’s liberty in a generation, to say nothing of its deleterious impact on LGBTQ people and communities of color.

He is holding up the federal judicial end of what has chiefly been a state and legislature-based battle, to the detriment of us all.

I.

“It is presumed that the reasonable observer is acquainted with this tradition [of legislative prayer] and understands that its purposes are to lend gravity to public proceedings and to acknowledge the place religion holds in the lives of many private citizens,” wrote Kennedy in his majority opinion, “not to afford government an opportunity to proselytize or force truant constituents into the pews.” He added that those who feel “excluded or disrespected” by such public prayer should ignore it because “offense … does not equate to coercion. Adults,” he chides, “often encounter speech they find disagreeable.”

Much of the majority opinion turns on this question of “coercion,” which for Justice Kennedy must be conscious, and explicitly named. Arguing that the Town of Greece’s legislative prayers “neither chastised dissenters nor attempted lengthy disquisition on religious dogma,” Kennedy avers that legislative bodies are not in any sense applying pressure to those of non-Christian faiths by requiring such prayer sessions because they are putatively optional and no one is holding a gun to the heads of legislators or petitioners. As Justice Thomas put it, “peer pressure, unpleasant as it may be, is not coercion.”

This faulty understanding of power is, indeed, what is disarming the sentinels of constitutional authority and licensing a perilously narrow reading of one religion to become the sine qua non of “religious freedom” in our society. This mentality is what is at work behind every “conscience clause,” behind every anti-LGBTQ “religious freedom restoration” law, and behind attempts to limit the availability of contraception.

Visible in Justice Kennedy’s other rulings is an equal disdain for the positive assertion of public rights—and it is important to focus on him because his occasional dissents from the four hardline conservatives on the Court are just as important as his concurrences with them; he is the keystone that makes many 5-4 splits happen, after all.

II.

Justice Kennedy’s reasoning has always borne a libertarian streak with consistency and pride.

He was feted by many liberals for helping to strike down the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA)—a surprise to some who had come to group him with the Court’s more deeply conservative members. But he voted to strike down DOMA because of the way in which the law was constructed, as a government intrusion that deliberately segregated marriages. That same summer he also voted to gut the Voting Rights Act (VRA) by striking down its fourth article, which provided for federal review of all changes to voting laws in certain jurisdictions that had a long history of legally expressed racial prejudice.

The difference? The VRA is legislation that is designed to level the playing field by using the power of the federal government to empower people of color. It is this species of legislation, born of a radically democratic philosophy, that is anathema to Kennedy. DOMA, by contrast, was about a negative right—the right to have a marriage unmolested by government interference. Marriage is a pre-existing right, not a new one created by any legislation. Thus DOMA was an intrusion that the libertarian Anthony Kennedy understood to be one compelling him to rule in favor of LGBTQ people—although he signed onto the most narrow version of the ruling, to be quite sure, which did not overturn same-sex marriage bans at a stroke but rather just disapprovingly punted the matter back to the states.

For Kennedy, it is the vision of a government meddling in the affairs of non-governmental actors that fills him with such dread, and constitutes the only exercise of power that he considers to be truly coercive. All other forms of prejudice, he seems to suggest, are best dispensed with privately through the thickness of one’s hide and little else.

Yet these informal swarms of prejudice are very real and profoundly coercive.

Kennedy makes an all too common mistake when he suggests that cases like Town of Greece, which orbit questions of “exclusion,” are really just about hurt feelings. In an op-ed to the Washington Post about the case, conservative columnist George F. Will expressed that sentiment perfectly when he groused that “[t]aking offense has become America’s national pastime; being theatrically offended [signifies] the delicacy of people who feel entitled to pass through life without encountering ideas or practices that annoy them.”

The echoes of Kennedy’s one-liner about “adults” are quite clearly discernible.

This bloviating about offendedness is the refusal to see material harm in certain social formations that may well manifest as speech but also constitute acts unto themselves, which then materially reshape the world around them. Words, after all, do something; it is that fundamental truth which underscores the civil libertarian’s enthusiasm for speech.

Indeed, at least one supervisor in Virginia is taking this ruling as his cue to materially exclude non-Christians from being represented in his city’s invocations. These are not just words; something is being done.

III.

Yet, informal domination is a ghost story to Justice Kennedy. Thus it is that he lends majesty and grandeur to far grubbier efforts to erode the freedoms of women and minorities, in no small measure by licensing policies that constitute such groups as de facto others merely because there is no de jure text calling for their subjugation. A business can deny trade to an LGBT person as an expression of their religious beliefs, and this is not discrimination because no government law is actually the origin-point of the intrusion—a pharmacist can deny a woman Plan B, and a town or city may hold legislative prayers for the Christian faith but no other, for the same reason.

Justice Kennedy seems to say that as long as they’re nice about it, such behavior is tolerable, and can be “ignored” by “adults” of good will. But this is not citizenship. We do not have a democracy if collectives of some citizens are allowed to practice discrimination against others in ways that are completely unchecked. Liberty is not about survival of the fittest.

It is worth noting that a major trend at both the Supreme Court level and the state legislative level has been to compel victims of discrimination to stand alone, and without government assistance. Whether it was Lilly Ledbetter, political actors without access to great wealth, people of color in Southern states, or women working at Walmart, the Court has suggested that there were either severely truncated federal remedies for them or simply none at all.

In other words, women and minorities are increasingly unable to repair to the standard of our shared nationhood, which the federal government (often referred to as “public” for good reason) is meant to represent. In denying the women of Walmart the ability to sue as a class, for instance, the Supreme Court shattered the kind of collective power needed for people of minimal means—in other words, the ordinary citizen—to challenge large institutional collectives like corporations. Each woman, then, was made to sue for sex discrimination as an individual, not as a group, in spite of the clear pattern of sexism at many stores.

You can guess which side Justice Kennedy was on in that case, of course.

This erosion of the collective power of minorities has been a hallmark of the Roberts Court’s jurisprudence, and it is mirrored by far-right state legislatures that are determined to dynamite the pillars of collective redress. Such cases and laws compel the government to stand idly by as private citizens do violence to one another, in other words.

IV.

If, as many fear, the Supreme Court rules in favor of stores like Hobby Lobby in that pivotal case on contraception, it will be yet another blow to the power of citizens to appeal to the government to defend the rights we all supposedly have. The “religious freedom” of a powerful institution—in this case, a corporation—trumps the rights of women to bodily autonomy and the health care they earn through their labors. (We ought to have a full-on right to health care, but that’s another polemic entirely.)

Justice Kennedy is, doubtless, expressing his sincere fealty to his libertarian ideals, but the naiveté of his conception of power is profoundly magnified by the prodigiously convex lens of the Roberts Court’s conservatism. It constructs citizenship as a state-of-nature wilderness wherein all must take up arms against all to ensure some happy equilibrium of rights and duties, where no embattled minority or less-privileged group can appeal to a collective entity like government to level their playing field.

Thick skin and battle armor are all that this particularly debauched form of citizenship requires.

The crowdsourcing of bigotry requires government to step aside and deny the tools of redress to the powerless. Because Justice Kennedy and those like him believe that coercion can only come from a law that explicitly says it is discriminating, and that anything else is an ignorable “offense” that does little more than wound “feelings,” they allow the government to step back from its vital role in providing women and minorities with the collective power they need to stand on an even footing with established, privileged, or powerful collectives. This can be the institution of Christian religion or the Catholic Church, a corporation, or the traditionalism of anti-LGBT prejudice that makes itself manifest in thousands of microaggressions that police space and behavior.

Justice Kennedy has helped create the space for those like the Mississippi state legislature to make it harder for its own citizens to guarantee their rights when it comes to such actors. We are all the poorer for it.