Four Ways to Create Culture Change Around Abortion

Culture change is distinct from policy change and health-care access, but it’s just as important. It’s difficult to imagine long-term policy gains without doing the hard work to change norms, beliefs, and behavior.

Take a moment to think back to where you were in November 2010. Harry Potter and the Deathly Hollows, Part 1 was in theaters. The song you couldn’t get enough of (or get away from) was Ke$ha’s “Tik Tok.” In the political world, the Tea Party had just ascended to legislative power and a slew of anti-choice governors came into office.

Dismayed and depressed by this political turn, I wanted to do something, anything, to show that although they’d won in the polls, anti-choice advocates weren’t winning in the streets. Or, in this case, online. I read a blog post comparing “coming out” about abortion and “coming out” about being gay. It seemed like an easy formula in my mind: “coming out” = culture change.

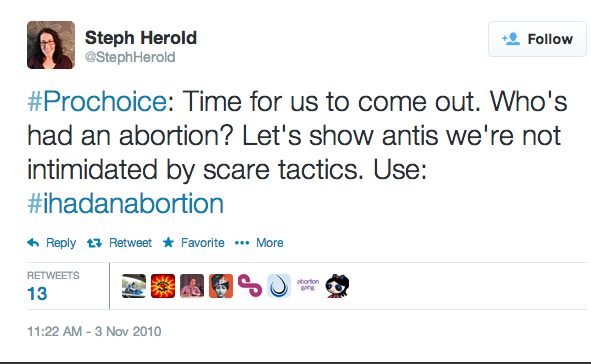

At the time, using Twitter as a tool for social change was still a relatively new strategy, and I wanted to give it a shot. So I sent the tweet that you see above. I didn’t know what would happen, but I didn’t think it would be a big deal. I actually sent the tweet and then headed to the gym.

Over the course of the day, there were over 10,000 tweets on the hashtag #ihadanabortion. At first, the hashtag accompanied tweets in which people shared their own abortion experiences. Later, anti-choice advocates joined in to shame people sharing their stories on the hashtag. And then came the media. Stories about the hashtag appeared everywhere from feminist-leaning outlets like Jezebel and Salon to mainstream media like CNN and the Washington Post. I had no idea this would happen. Obviously the hashtag struck a nerve, and I was excited.

Starting a trending topic on Twitter led me to think more deeply about what creating culture change really means. Seeing thousands of tweets on a hashtag you start feels pretty incredible. But what happens the next day, the next week, or the next month? I had what shame expert Brene Brown calls the “vulnerability hangover.” Starting the hashtag felt great. And then I woke up the next day thinking, “What did I do??” I asked all these people to talk about their abortions only to be attacked by anti-abortion activists and ridiculed by mainstream media?

I really wanted to claim that my hashtag made a difference, but I didn’t have concrete evidence. I knew I had made a difference in the lives of a few dozen women and perhaps demonstrated the power of social media. But I kept wondering if I actually affected the broader stigma system. Did I contribute to changing the big picture?

Looking back, my hashtag was based on a simplistic understanding of culture change. In the wake of the media coverage of the hashtag, I began to deepen my understanding of culture change strategies by studying other social justice movements. What I learned validated my frustration with the seemingly ephemeral nature of my online activism; it turns out you often can’t create meaningful, lasting culture change alone and in one day. But my investigation also solidified my belief that culture change efforts are imperative to the policy and health-care access work that our movement is doing. Ignoring culture change to focus on policy and health care may garner some short-term wins, but leaves you without a long-term aspirational vision for change. In other words, a movement that is built only on two legs—policy and health-care access—cannot stand. We need that third leg: culture change.

Culture refers to our beliefs, customs, and norms and how these factors vary by age, race, ethnicity, religion, and other demographic factors. In order to achieve our vision of a world in which all people have the rights, resources, and respect to make their own decisions about their reproductive lives, we need to have a sophisticated approach to culture change. We need to invest in innovation, invention, discovery, and contact.

What exactly do culture change strategies do and how can they add to policy strategies as we move forward our vision?

Address silence, shame, and fear. People keep silent about their abortions for many reasons, including for fear of the consequences of coming out. Culture change initiatives such as private support groups can address this fear by giving people who’ve had stigmatized experiences a chance to connect with each other in a private space. This allows people to come out of isolation and increase their sense of connection to people who understand their experience. It also gives people an immediate support group to aid them in figuring out if and how to disclose their experiences to loved ones in their lives.

Increase visibility. Many stigmatized experiences are concealable—you can’t tell by looking at someone that they’ve had an abortion. So many people don’t realize that they likely know someone who’s had an abortion. Increasing the visibility of marginalized reproductive experiences (such as filming your abortion for millions to see) shows that people who have stigmatized experiences are normal, familiar, and acceptable. Once people know that someone close to them is affected by these experiences, they are likely to be more empathetic toward that experience. This can only mean positive outcomes for us in the policy realm.

Transform negative attitudes, beliefs, and stereotypes. Culture change strategies aim to transform the attitudes and beliefs that contribute to stigma, often by raising awareness about personal experiences. Culture change also addresses discrimination, emphasizing changing behavioral norms in communities and institutions, including behaviors like shaming, not providing services, or condemning people from the pulpit. Creative community- and institutional-level interventions can address these norms, and measure whether targeted attitude change around abortion leads to different behavior at the polls.

Deconstruct myths and misperceptions. This might include misperceptions about the acceptability of judgmental attitudes toward abortion, or myths about the way abortion is provided. In some communities, the public perception is that most people are anti-abortion, but the reality is that, when asked, most people say they would support a friend or family member who needed an abortion. What would happen if you exposed this misperception? If we let people know that they are not alone in their beliefs? What kind of policy change would be possible if we asked questions such as, “How do you think a person who’s had an abortion should be treated?” instead of asking if abortion should be legal? If we stopped asking people to judge the morality or legality of the decisions of their friends and family members and instead asked them to provide support? How many people could we welcome into the pro-choice and reproductive justice communities and activate to create policy change?

Culture change is distinct from policy change and health-care access, but it’s just as important. It’s difficult to imagine long-term policy gains without doing the hard work to change norms, beliefs, and behavior. We’ve seen first-hand that without culture change, no policy change will be long lasting. We have Roe v. Wade, yet that certainly hasn’t guaranteed the right to accessing an abortion in the United States. As we get ready to gear up for another presidential election, we have to remember to prioritize culture change. It’s time to make shift happen.