What Janet Mock Can Teach Us About Womanhood and ‘Realness’

While the media has moved on from Piers Morgan's awful interview to the next topic du jour, many of us are still getting around to unpacking Janet Mock’s story and the struggles facing trans people that, unfortunately, continue to be overlooked by mainstream media for the more “titillating” aspects of their stories.

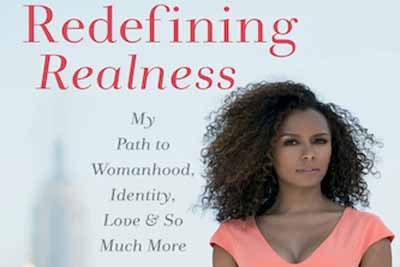

Janet Mock’s memoir, Redefining Realness: My Path to Womanhood, Identity, Love & So Much More, does what a 2011 Marie Claire article about her, and many of the other stories told about people coming out as transgender, did not do: It tells her truth in a way that’s not meant to be flattering or heroic, just real.

Since the publication of her book, Mock, a former editor of People.com, has been very clear that her story is not the story of trans women of color. In an interview with Bitch magazine about her book, she said, “This is one story, one book. I am not speaking for all trans women of color; I’m telling my story. To assume I’m somehow representative of all trans women is unfair. I’ve had access and role models and privileges many trans women of color don’t, but I still struggled, and Redefining Realness is about how I got from there to here.”

Redefining Realness may be about one trans woman of color, but it’s a story everyone should read, because the issues she confronts—including identity, poverty, sexual abuse, and self love—are things that are, in one way or another, within our power to change. And for that reason people should be, and seem genuinely interested in, having public conversations about the needs of trans people.

A recent Piers Morgan interview of Mock, however, showed how far the general public has to go when discussing the stories of trans people. After the interview, which I won’t detail here (read Zack Ford’s ThinkProgress piece about it for more, or watch Stephen Colbert get into it with Mock here), Jamilah King at Colorlines nails it when she writes that the interview “was upsetting for many reasons, but especially because Morgan’s questioning implied there’s an inherent deception involved in being transgender.”

It’s a logic that says that being transgender is a choice, a costume, a scheme put on to dupe cis men. It’s also the same logic at the core of so-called “trans panic” legal defenses, in which cis men accused of killing trans women have, often successfully, argued in court that they were “provoked” to attack their victims after discovering their biological sex. It’s a warped sense of power cloaked in patriarchy that has dug early graves for women like Gwen Araujo and Angie Zapata, teenagers who were violently killed for being themselves.

And even while the Piers Morgan segment and subsequent firestorm have come and gone, transgender people continue to face many of the struggles outlined in Mock’s eloquently written memoir, and much more. That’s the hard-fought win of the written word, in my opinion. Because while the media has moved on to the next topic du jour, many of us are still getting around to unpacking Janet Mock’s story and the struggles facing trans people that, unfortunately, continue to be overlooked by mainstream media for the more “titillating” aspects of their stories. In 2013, for instance, the media couldn’t get it together after Chelsea Manning came out as a trans woman. (Facebook, however, is leading the way for social networking sites by allowing its users in the United States to customize their gender identification.)

Mock shared her truth with her family when she was 13, but her struggles with gender identity began way before then. In her book she describes what it was like growing up in California with her father, who constantly policed her gender, and later back in Hawaii, where she was born, with her mother, who was never able to live up to the image Mock “had projected onto her, the image of the perfect mother,” as she often put the men in her life before Mock and her other children. Mock’s relationship with her younger brother, Chad, also was strained at times when they both were figuring out their respective identities. Mock admits in the book to worrying Chad would be disappointed she was not “being a better big brother” while they were growing up and she was “learning the world, unsure, unstable, wobbly, living somewhere between confusion, discovery, and conviction.” She also had a difficult relationship with many of her schoolmates and educators who failed to “grasp the varied identities, needs, and determinations of trans people” and therefore made her formative years miserable. All of these relationships were managed by Mock under dire circumstances; Mock’s family, both in California and Hawaii, was no stranger to poverty and addiction.

Without support and guidance from her personal network and other trans girls and trans women, without a memoir like Redefining Realness to guide her, she became isolated and an “easier target” for a sexual abuser.

Eight-year-old Mock was sexually abused for two years by her father’s girlfriend’s son and felt certain she “had asked for it” because “this is what happens to sissies,” so she didn’t tell anyone about it. As Mock writes:

The fact that I was feminine and wanted to be seen as girl was something I held close. I was prime prey. He could smell the isolation on me, and I was lured into believing the illusion that he truly saw me. I was a child, dependent, learning, unknowing, trusting, and wiling to do what was asked of me to gain approval and affection.

According to research from the National Center for Transgender Equality and the National Gay and Lesbian Task Force, 12 percent of the 6,450 transgender and gender non-conforming survey respondents reported experiencing sexual violence while in grades K-12. The 2011 study also found that 78 percent were harassed in K-12 and 35 percent were physically assaulted. In addition, an alarming 41 percent reported attempting suicide, compared to 1.6 percent of the general population, “with rates rising for those who lost a job due to bias (55%), were harassed/bullied in school (51%), had low household income, or were the victim of physical assault (61%) or sexual assault (64%).”

In her book, Mock explains how it was only after she met her trans friend Wendi—someone whom she could finally see herself in, thus allowing her to begin “openly expressing [her] femininity”—that she felt courageous enough to share her truth with her family. Wendi also helped Mock access the hormones that would help her become more fully herself, sharing her prescription, which was covered under her grandmother’s insurance, until Mock was able to get her own prescription with her mother’s assistance. Mock’s ability to get hormone therapy the way she did before her mother took her to a doctor was a privilege she acknowledges. Indeed, the majority of trans youth are unable to access the health care they need, and unfortunately under our current health-care system that only gets more difficult in adulthood, as Tara Murtha explains here.

Mock described her initial years with Wendi, who is still her good friend:

When I think of this time with Wendi, I’m reminded of the line from Toni Morrison’s Sula: “Nobody was minding us, so we minded ourselves.” I was her sister … We needed each other to create who we were supposed to be.

When she first talked to her mother, she wrote in her book that she conflated her gender and sexuality, saying she was gay, because like most trans youth she “didn’t have a full understanding of” gender. “Saying ‘I think I’m a girl’ would have been absurd for many reasons,” wrote Mock, “including my fear it would be a lot for my mother to handle. I didn’t know trans people existed; I had no idea that it was possible for thirteen-year-old me to become my own woman. That was a fantasy.”

The way that she tells her story, combining references to television shows, pop stars, and real-life scenarios all of us can relate to (such as a first bike ride, or first kiss) with what it was like existing in a world surrounded by people who couldn’t grasp what she needed or who she was—her identity—is stirring.

For example, there’s a passage early in the book when she’s describing her father, who we learn later in the book was addicted to crack cocaine. Her father spent much of her childhood trying to fix her. Years after, he explained to her that “he took it upon himself to change what he believe to be my ‘soft ways.’” She wrote:

“I didn’t want to see it, man,” he admitted. “I tried to be tougher on your ass. I thought I could fix you.”

It would take decades for my father to realize that I didn’t need fixing, and he should have been more focused on his marriage, which was plagued by infidelity, failed expectations, and youth.

The same could be said of many state legislatures that burn midnight oil, wasting taxpayer money to “fix” the “problem” of marriage, or women’s reproductive rights, or health-care reform. They’re so focused on what they perceive as problems, instead of focusing on how to address the actual problems of LGBT violence, unemployment, and high medical costs for those most in need.

Transgender people have a much more difficult time earning a living than other people in the United States. Research shows a staggering 97 percent of transgender workers have been harassed in the office, and 26 percent have lost their job because of their gender status. As such, many trans people are forced to work “in the underground economy” for money (16 percent of respondents in the 2011 study reported doing so).

Growing up without financial privilege, Mock, like other trans women of color, had to take steps to accomplish her goals “toward greater contentment” that at turns compromised her integrity. Where Mock grew up, trans women would engage in sex work in downtown Honolulu. As she explained it:

They came to Merchant Street and took control of their bodies—bodies that were radical in their mere existence in this misogynistic, transphobic, elitist world—because their bodies, their wits, their collective legacy of survival, were tools to care for themselves when their families, our government, and our medical establishment turned their backs.

Which is how Mock, a high school honor student, a class representative, and someone “who wanted to do bigger, better things” ended up working there to help pay for her surgery.

This narrative of trans people taking illegal measures to live their truth is one that has gained some traction in the mainstream recently. On the Netflix original series Orange Is the New Black, trans actress and activist Laverne Cox’s character, also a trans woman, is serving time in prison for credit card fraud, which she did to pay for her genital reconstruction surgery. But what many of these stories about reconstruction surgery fail to address is what transgender people are seeking that’s “grander than the changing of genitalia.” In Mock’s case, she says, “I was seeking reconciliation with myself.”

Mock wrote, “Having genital reconstruction surgery did not make me better. The procedure made me no longer feel as self-conscious about my body, which made me more confident and helped me to be more completely myself. Like hormones, it enabled me to more fully inhabit my most authentic self.”

The sacrifices transgender people make, often out of desperation, should not be turned into fantasy or sexualized. But that’s what Piers Morgan’s team did when they asked via Twitter, “How would you feel if you found out the woman you are dating was formerly a man?” How about asking Janet Mock what it was like for her, not just when she shared her truth, but what her life has been like and what life is like for transgender people in general who lack support and basic services like health care, employment, or housing because of discrimination practices embedded in the system? As Mock, who went on to earn a master’s degree in journalism from New York University, explains it, we can do more than these “tried-and-true transition stories tailored to the cis gaze.”

Moreover, “transitioning” was not the end of Mock’s journey. She goes on to explain how upon joining the LGBT activist community she quickly noticed, “Women, people of color, trans folks, and especially folks who carried multiple identities were all but absent” from the tables and conversations. “My awakening pushed me to be more vocal about these issues, prompting uncomfortable but necessary conversations about the movement privileging middle- and upper-class cis gay and lesbian rights over the daily access issues plaguing low-income queer and trans youth and LGBT youth of color, communities that carry interlocking identities that are not mutually exclusive, that make them all the more vulnerable to poverty, homelessness, unemployment, HIV/AIDs, hyper-criminlization, violence, and so much more.”

Throughout her book, Mock reminds us that trans people want the freedom to define gender and who they are in their own terms; so let them. “We must abolish the entitlement that deludes us into believing that we have the right to make assumptions about people’s identities and project those assumptions onto their genders and bodies,” wrote Mock. “It is not a woman’s duty to disclose that she’s trans to every person she meets. This is not safe for a myriad of reasons. We must shift the burden of coming out from trans women, and accusing them of hiding or lying, and focus on why it is unsafe for women to be trans.”

I would add that we should also focus on talking to trans girls about identity, womanhood, and breaking the cycle of “othering.” With help from Mock’s #GirlsLikeUs movement, “girls … with something extra” and “just girls” are being empowered to overcome such hostility against them online. Mock explains on her site about the creation of #GirlsLikeUs in 2012 that young women using the Twitter hashtag will “find like-minded sisters whom we can embrace and love and connect with because it’s only in our connecting that we will be more powerful and ensure that our voices and our lives and our struggles and joys matter.” (And judging by this account on the tag’s one-year anniversary, it has enabled connections and much more.) The #RedefiningRealness Tumblr is an extension of that.

“When I am asked how I define womanhood, I often quote feminist author Simone de Beauvoir: ‘One is not born, but rather becomes, a woman.’ I’ve always been struck by her use of becomes,” wrote Mock. “Becoming is the action that births our womanhood, rather than passive act of being born (an act none of us has a choice in). This short, powerful statement assured me that I have the freedom, in spite of and because of my birth, body, race, gender expectations, and economic resources, to define myself for myself and for others.”