Dylan Byers and the Scourge of Privileged Defensiveness

Byers' response to Ta-Nehisi Coates calling Melissa Harris-Perry "America's foremost public intellectual" illustrates an important problem: People in positions of privilege frequently have blind spots for the work, achievements, and culture of people who are different than them.

MSNBC’s Melissa Harris-Perry recently apologized, quickly and sincerely, after a lighthearted segment on her eponymous show veered off the rails and ended up in an insensitive place, with panelists mocking Mitt Romney’s adopted grandson, who is Black.

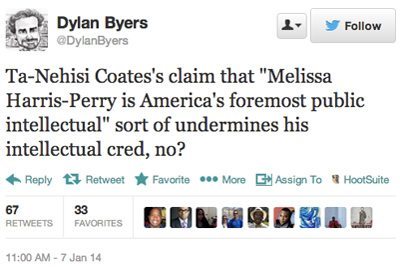

In response, The Atlantic’s Ta-Nehisi Coates penned a nuanced defense of Harris-Perry, calling her “America’s foremost public intellectual.” That turn of phrase didn’t sit well with some, most notably Politico media critic Dylan Byers, who tweeted:

The condemnation of Byers by #BlackTwitter and other media figures was swift. But Byers dug his heels in, writing an article rebutting Coates, in which he was extremely defensive. Byers claims he was “berated on Twitter as ignorant, racist and worse,” and claimed that the people criticizing his tweet were “blind.”

As Coates noted, it’s fine for Byers or anyone else to disagree with his opinion that Harris-Perry is America’s foremost public intellectual, but implying that this view undermines Coates’ credibility was a bridge too far.

Based on this exchange, I have a new rule for 2014: The people who benefit from the most privilege—whether based on their race, gender, orientation, economic status, or ability—need to resist the initial impulse to be defensive when called out.

Pointing out a person’s privilege is not an indictment of their character or integrity; it’s about calling attention to the benefits a person is granted based on their station in society and how they act on those benefits, not who they are in their heart.

Privilege is the flip side to discrimination in many respects and manifests itself often in the form of blind spots.

For example, in October I wrote an article arguing that journalists who were being hyperbolic about the problems with the Obamacare website—full-time journalists who generally have health insurance through their employers—may have been letting their privilege cloud some of their reporting. If you already have insurance, you might be less patient with a glitchy website than someone who, like me, was uninsured before I signed up for Obamacare. Many of the responses to my critique were mostly off the mark because they were defensive in nature, even going as far to imply that I was bitter.

As Coates put it, with regard to Byers:

Here is the machinery of racism—the privilege of being oblivious to questions, of never having to grapple with the everywhere; the right of false naming; the right to claim that the lakes, trees, and mountains of our world do not exist; the right to insult our intelligence with your ignorance. The machinery of racism requires no bigotry from Dylan Byers. It merely requires that Dylan Byers sit still.

It’s not about racism, it’s about privilege. And Byers’ response demonstrated his lack of understanding of how privilege works. Byers writes:

I do not believe Harris-Perry is “America’s foremost public intellectual,” meaning that of all the public intellectuals in this country, she is not the most influential or important. What I suggested was that stating as much called one’s own intellectual credibility into question, because it would take leaps and bounds to come to the conclusion that Harris-Perry occupies a more significant place in American intellectual thought than the towering figures who wear that title. That those figures are all white men is certainly an unfortunate result of America’s troubled history.

It should occur to Byers that Harris-Perry’s influence differs depending on which demographic you ask. It’s likely true that her influence among women is stronger than it is among men in Byers’ station. That he doesn’t consider her on his list of top public intellectuals doesn’t mean those people who do lack credibility.

This incident illustrates an important problem that people without privilege encounter all of the time: People in a position of privilege frequently have blind spots for the work, achievements, and culture of people who are different than them. Certainly, it’s true that we could never understand or know everything about cultures and people with whom we differ, but it’s privilege that allows the privileged to diminish those without it, based on their own lack of knowledge. In a subsequent tweet, when asked who he would consider as “America’s foremost public intellectual,” he tellingly described her as an “MSNBC weekend host,” overlooking the fact that she has a tenured position at Tulane University.

Even without ill intent, privilege can blind a well-meaning person to someone else’s struggle. Many men dismiss complaints about street harassment and view catcalling as a “compliment”—a view could only be held by someone who has never experienced persistent, unwanted harassment for simply existing in the public space. Men can walk around and not have to think about catcalling or being called a “b*tch” or a “c**t” on their morning commute, because street harassment is something they are privileged to not have to think about.

We do not live in a meritocracy. People of color know this all too well, but white Americans, and particularly those who lean conservative, often repeat the notion that hard work and personal responsibility will lead to success, even with a mountain of evidence to the contrary. People of color and women who do beat the odds and make it to the top of their fields are frequently dismissed and diminished for their laudable accomplishments.

Byers’ own “Journalists to Watch in 2014” list provides a perfect example of this. You will be unsurprised to hear how many people of color appeared on that list:

Zero.