Are Sex Workers’ Rights Becoming Thinkable?

Recent political developments suggest some growing political awareness of sex workers as human beings.

In most countries, the concept of sex workers’ human rights has been unthinkable for the last few millennia. As Bubbles, the co-founder of the blog Tits and Sass, has observed, “Sex workers are generally portrayed as victims or punchlines.”

Recent political developments, however, suggest some growing political awareness of sex workers as human beings. On December 20, Canada’s Supreme Court ruled in favor of the plaintiffs in Attorney General of Canada v. Terri Jean Bedford, Amy Lebovitch, and Valerie Scott. These three women, self-identified sex workers, filed suit in 2007 because they felt three provisions in the Canadian Criminal Code violated their constitutional rights.

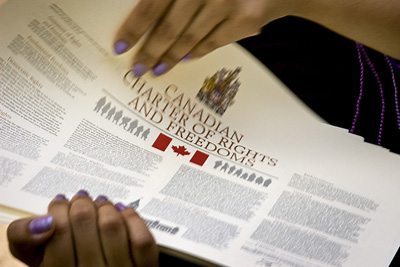

After six years of weaving its way through the courts, their case resulted in a unanimous decision striking down laws against keeping or being found in a brothel (or “bawdy house,” to use the law’s term), living on the avails (profits) of selling sex, and “communicating in public for the purpose of prostitution” (street soliciting). These provisions, the Court ruled, violated the right to “security of the person” guaranteed by Canada’s Charter of Rights and Freedoms enacted in 1982. The Globe and Mail, Canada’s nationally distributed newspaper, described Chief Justice Beverley McLachlin’s decision (on behalf of the Court) as not being “about whether prostitution should be legal or not, but about whether Parliament’s means of controlling it infringe the constitutional rights of prostitutes.”

The decision states:

Parliament has the power to regulate against nuisances, but not at the cost of the health, safety and lives of prostitutes. … The prohibitions all heighten the risks. … They do not merely impose conditions on how prostitutes operate. They go a critical step further, by imposing dangerous conditions on prostitution; they prevent people engaged in a risky—but legal—activity from taking steps to protect themselves from the risks.

The Court agreed on a one-year suspension of the ruling to give Parliament time to respond. If lawmakers choose to pursue passage of new prohibitions, they will be obliged, under the ruling, to ensure that they do not violate sex workers’ right to safety.

Prostitution, per se, is not illegal in Canada, but the decision and other laws circumscribe its practice. Laws against brothel keeping specifically put indoor sex workers at risk of arrest, and the ban on living on the avails criminalizes a sex worker’s children and other people who are supported by her earnings. The public communications laws severely affect the estimated 5 to 20 percent of Canadian sex workers who are street-based. By compelling them to complete negotiations quickly (in order to avoid arrest), it deprives them of the time needed to assess the potential risk of going with a prospective client.

The Pivot Legal Society, Downtown Eastside Sex Workers United Against Violence, and the PACE (Providing Alternatives Counseling and Education) Society all worked in coalition with the Bedford petitioners and other sex worker groups to advance the case. When Pivot was allotted time to address the Supreme Court directly, a collective decision was made that Pivot’s legal director, Katrina Pacey, would use the time to “paint a picture” for the justices of the violence sex workers routinely experience under existing laws. They agreed that Pacey would emphasize the “Bad Date Sheet,” a tool used by sex workers to record and share descriptions of clients known to be dangerous and predatory. Pacey told the justices that “having time to adequately screen a client means having time to refer to the information on this sheet … and it can be a life-saving measure … time to communicate, time to screen, can mean the difference between life and death for a sex worker.”

This struck a deep chord because of the epidemic of missing and murdered women—most of them sex workers—that Canada has experienced in the last three decades. At the center of this was Robert Pickton, a serial killer in British Columbia who told an undercover police officer that he had killed 49 women and wished he could have made it an even 50 before his arrest. Pickton was charged in 2002 with the murders of 26 women, most of them sex workers and/or drug users from Vancouver’s Downtown Eastside neighborhood. He was convicted in 2007 of killing six of them, with the 20 other charges stayed, and sentenced to life imprisonment.

Pickton is far from an anomaly. Seattle’s Gary Ridgway (the “Green River Killer”) was convicted in 2003 of murdering 48 women, and later confessed to killing 71 in all. He said he picked sex workers specifically because “I knew they would not be reported missing right away and might never be reported missing. I picked prostitutes because I thought I could kill as many of them as I wanted without getting caught.” Meanwhile, the search for the alleged Gilgo Beach serial killer in Long Island, New York, is ongoing. The first woman went missing in 2007, and to date ten to 14 of the bodies identified on that isolated section of beach are thought to have been his victims. As in the cases above, the New York police have been repeatedly accused of insufficient action because many of the murdered women were sex workers.

After hearing Pacey’s statement to the Court, Chief Justice McLaughlin wrote in her opinion, “If screening could have prevented one woman from jumping into Robert Pickton’s car, the severity of the harmful effects [of the law] is established.”

A breakthrough of a different type, but similar in proportion, occurred in South Africa on December 10, when the South African National AIDS Council (SANAC) launched its National Strategic Plan for HIV Prevention, Care and Treatment for Sex Workers. The Sex Worker Education and Advocacy Taskforce (SWEAT) and Sisonke (a South African movement advocating for the rights of adult, consenting sex workers) were pivotal in the plan’s development and describe it as a “comprehensive rights- and evidence-based approach to HIV interventions within the sex worker key population.” Maria Stacey, SWEAT’s deputy director, added, “Following World Health Organisation guidelines on HIV prevention amongst sex workers, the Plan does advocate for the decriminalisation of sex work.”

SANAC, an entity made up of government ministries, civil society organizations, and private sector corporations, is charged with building and coordinating the HIV and AIDS response for a country with the world’s largest population of people living with HIV. This new program launch is a historic development in what has been a prolonged political battle. When the SANAC board approved a final draft of its 2012-16 National Strategic Plan on HIV, Sexually Transmitted Infections, and Tuberculosis (commonly referred to as the 2012 NSP) in November 2011, the draft contained language directing the Department of Justice and Constitutional Development and the South African Law Reform Commission to “take urgent steps to finalise the legislative reform process. … This must result in the tabling of a bill to decriminalize adult sex work by no later than 30 June 2013. Thereafter, SANAC must closely monitor the law reform process in Parliament.’’

When formally issued on World AIDS Day a few weeks later, however, SANAC’s plan omitted that language, replacing it with the following: “Decriminalisation of sex work is a matter that has been a subject of debate and society should continue to deliberate on the matter until final resolution.” As one SANAC member commented, “Government ministers, officials, other sectors and NGOs at the meeting endorsed this [decriminalization] as a key, evidence-based. Now, in one week, all that has dissolved.”

The sex workers’ rights and HIV prevention advocates who had been working for over a decade to get the board-approved language into the 2012 NSP saw this deletion as, once again, fatally dismissive of sex workers’ lives. Data from 2005 (the most recent year for which data is available) showed an HIV prevalence of 43 percent among female sex workers surveyed in Johannesburg, evidence of the government’s disregard for their need for effective HIV prevention interventions.

The two-year turnaround from this political betrayal to the launching of a national program dedicated to their needs is attributed to (among other factors) the 2012 hiring of SANAC’s new CEO, Dr. Fareed Abdullah, and the government’s decision to make SANAC an independent entity, answerable to all its constituencies. Abdullah came to the job with a decade of experience “pioneering” innovative HIV programming in South Africa, as well as service at the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria (the Global Fund) and the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative (IAVI). The first grant he authorized from SANAC’s newly independent budget was to SWEAT.

The new National Plan for HIV Prevention, Care and Treatment for Sex Workers not only includes the provision of a full package of sexual and reproductive health services to an estimated 153,000 sex workers in the country (including sexually transmitted infection screening and treatment, post-exposure prophylaxis for rape and sexual assault, contraception, and peer support, as well as education, condoms, and lubricant) but also funds measures to reduce violence and human rights abuses against them. In an interview shortly before the ICASA launch, Abdullah said that “[t]his approach allows the social capital of the sex work community to be strengthened—which we know to be protective for HIV.” He added, “The time has come for us to suspend our moral judgments in respect of sex work in the interest of the public health of the nation and human rights.”

Interestingly, former U.S. ambassador Mark Dybul was among the panelists at the ICASA session where the new plan was launched. Currently the CEO of the Global Fund, Dybul was one of the founding architects of PEPFAR, serving as U.S. Global AIDS coordinator from 2006 to 2009. In his remarks at the ICASA launch, Dybul described the fact that HIV-positive sex workers are 12 times less likely to receive antiretroviral treatment than other people living with HIV as “appalling,” and said that SANAC’s plan demonstrated “what needs to be done, not only in South Africa but everywhere.” One wonders if this evolving awareness—manifested in two countries and by the head of the Global Fund so recently—will become evident in U.S. policy anytime soon.