#SolidarityIsForTheAbleBodied, and Feminism’s Ableism Problem

While the hashtag shined a light on how ableism is a systemic issue in all political and societal respects, it also revealed something that has long been known by some, but that has been unrecognized by others: that feminism has an ableism problem.

“The world, as imperfect as it is, it is not built for the disabled community,” Neal Carter said over the phone one late November morning.

At the time, it had been a few weeks since #SolidarityIsForTheAbleBodied trended on Twitter, and Carter, who was born with spina bifida, was explaining the motivation behind the hashtag he created. Both an extension of his #Ableism101 tag and a play on Mikki Kendall’s work starting #SolidarityIsForWhiteWomen, #SolidarityIsForTheAbleBodied aimed to spark a conversation among people with disabilities who “have to fight, and hard, to adapt … to fit into the world,” Carter, a political consultant who lives in Maryland, said.

More so, it was meant to uncover the ableism experienced daily by the one in five people in the United States who has a disability. Just take a quick scan of the hashtag on Twitter, and you’ll read tweet after tweet of inequitable treatment. Denied government benefits because you’re not “disabled enough”? Check. Confronted by a “take the stairs” campaign when you use a wheelchair? Check. Avoided visiting the doctor’s because it’s inaccessible? Check. Told your depression is nothing but temporary sadness and that you should “just smile”? Check.

While #SolidarityIsForTheAbleBodied shined a light on incidents of able-bodied privilege from across the globe, showing how ableism is a systemic issue in all political and societal respects, it also revealed something that has long been known by some, but that has been unrecognized by others: that feminism has an ableism problem.

Plenty of well-known feminists have been known to use ableist speech—language invoking disability as a metaphor, typically in the pejorative. For instance, Caitlin Moran described her teenage self in her 2011 memoir, How to Be a Woman, as having “all the joyful ebullience of a retard.” On December 14, Lizz Winstead tweeted that President Obama is “surrounded by so many wildly gesturing loonies” in his day-to-day life, in response to the controversy surrounding the sign language interpreter at Nelson Mandela’s memorial. And last year Jezebel editor Jessica Coen defended against allegations that the blog is ableist by tweeting, “[T]he word ‘ableist’ is crazy and lame.”

In an article published earlier this year, Indiana University gender studies grad student Sami Schalk found that indirect ableism is “problematically habitual and historically consistent” in feminist texts, with feminists and women’s rights activists often invoking disability metaphors (such as “crippled,” “handicapped,” “lame,” “crazy,” and “insane”) to “represent inability, loss, and lack in a simplistic and uncritical way” for over a century.

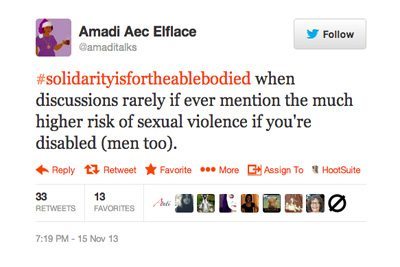

“The continued use of mental health ableism, especially by progressives, is my personal bugbear,” Amadi Lovelace, an active participant in #SolidarityIsForTheAbleBodied, said earlier this month. She said she’s unfollowed “many major noted feminists” on social media because of it. “We’re acculturated to consider disability as always a negative. We’re acculturated to think [of] disability as conferring inferiority. We haven’t come to a place yet where we are accepting the equality of disabled people,” she said.

Ableist rhetoric is only an overt measure of feminism’s ableism problem, though. For many activists and feminists with disabilities, like Lovelace, able-bodied privilege within the feminist movement is more defined by disregard—a dearth of conversations happening in the most prominent feminist outlets and among some of the more well-known feminists.

Disregard for the barriers women with disabilities face accessing reproductive health care, especially in places like Texas, Arizona, Iowa, Michigan, and Ohio, where the number of reproductive health clinics has shrunk due to restrictive legislation.

Disregard for the higher rates of poverty, which both exacerbates and is exacerbated by disability. The U.S. Census Bureau reports that 21 percent of people with disabilities are living below the poverty level, which is 10 percent more than those who are able-bodied. And, according to the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Labor Statistics, 13.7 percent of women with disabilities were unemployed in 2012, nearly 7 percent more than able-bodied women.

Disregard for how sexuality, relationships, and caregiving take shape for people with disabilities, continuing the ubiquitous belief that people with disabilities are asexual.

Disregard for the intersection of race and disability—disabilities are most prevalent among American Indians and Alaska Natives (29.9 percent), followed by Black and African-Americans (21.2 percent), whites (20.3 percent), Hispanics (16.9 percent), Native Hawaiian and Pacific Islanders (16. percent), and Asians (11.6 percent).

Disregard for how feminist and social justice spheres are too often exclusive of or inaccessible to people with disabilities.

As Lovelace noted, there’s disregard for the higher rates of sexual violence experienced by people with disabilities.

And then there’s the fact that, as predicted by Twitter user @RobinsToyNet, the most prominent feminist blogs and news sites have given #SolidarityIsForTheAbleBodied little—if any—attention even a month after the topic trended.

“We have seen in some place[s] the rate of being victims of sexual violence is doubled for women with profound physical, and especially mental, disabilities,” Lovelace said. “If you aren’t verbal, and you can’t tell what happened to you, I don’t think we even know. I don’t think we would know how many people are in those situations, especially ones being cared for in institutional care [who] have been victimized.”

The Bureau of Justice Statistics found that, in 2011 alone, serious violence (including rape and sexual assault) accounted for 43 percent of non-fatal violent crimes committed against people with disabilities; of that, 57 percent occurred against people with multiple disabilities. The bureau also found, from 2009 to 2011, the average annual percent of rape and sexual assault, robbery, and simple assault increased against persons with multiple disabilities.

Meanwhile, data collected by the Washington Coalition of Sexual Assault Programs (WCSAP) reveals that 83 percent of women with disabilities will experience sexual assault in their lifetime; only 3 percent of cases are ever reported. WCSAP also found that women with disabilities are more susceptible to having a history of intimate partner sexual violence, with a rate that is nearly two-and-a-half times higher than for women without disabilities.

Population-based studies examining rates of sexual violence against men with disabilities are limited, but a 2011 report published in the American Journal of Preventive Medicine (the first of its kind) found that, in Massachusetts, 13.9 percent of men with disabilities reported lifetime sexual violence—a rate nearly four times higher than for men without disabilities.

And, according to the World Health Organization, children with disabilities are nearly three times more likely to experience sexual violence than children without disabilities, with children living with mental or intellectual disabilities at nearly five times the risk. WCSAP also found that 54 percent of boys who are deaf and 50 percent of girls who are deaf experienced sexual abuse.

“There’s a knowledge gap because we find young kids—especially [those] who have profound disabilities, especially intellectual disabilities—aren’t taught about being safe in their own bodies, and that people can’t touch them or shouldn’t touch them,” Lovelace said. “We act like this isn’t something that’s possible, that people with profound disabilities have no sexuality. Also, there’s that mindset of innocence. People ascribe innocence to people with profound disabilities and they expect everybody will see them that way.”

But those are just the statistics. The stories are even more traumatic. Early this month, a 30-year-old woman with a mental disability filed a federal lawsuit against a West Sacramento police officer for reportedly sexually assaulting her in two separate 2012 incidents. In an unrelated case, Sacramento police arrested a veteran cop in December 2012 for the reported rape of a 76-year-old woman who experienced communication issues after suffering a stroke—a disability the defense hoped would discredit the victim. And in August of this year, another Sacramento man was sentenced to 11 years in prison for raping his 14-year-old stepdaughter, who has cerebral palsy.

That’s just one city. In July, a 55-year-old Philadelphia man confessed to raping a 15-year-old girl with severe mental and physical disabilities. In 2012, a 33-year-old man was charged with sexually molesting two young girls and raping an 18-year-old woman with a developmental disability at a care facility in Los Gatos, California. In 2011, a Des Moines, Iowa, woman who has an intellectual disability reported being raped several times over five days by fellow residents at a state-licensed facility. And, going back 13 years, Cobb County, Georgia, police arrested 20 suspects in the repeated gang rape of a 13-year-old girl with a mental disability, which happened over two days at two apartments.

Yet, these occurrences of sexual violence against people with disabilities are rarely discussed in the majority of well-established feminists outlets and blogs—statistics living in the shadows of the “intersectional understanding of feminism,” said Lovelace—despite the large network of disability activists and feminists with disabilities doing the work. It’s this exclusion that triggered disability rights activist Rachel Cohen-Rottenberg to disassociate from the feminist movement.

But feminists have the opportunity to change this tide. As with the intersections of race, class, gender, and sexuality, the feminist movement still has an opportunity to be more inclusive of people with disabilities, both in addressing these sweeping issues more frequently and actively making spaces, materials, websites and other methods of outreach accessible. If #SolidarityIsForTheAbleBodied has taught us anything, achieving this inclusivity is just a matter of listening and broadening your horizons, Lovelace said.

Or, as African activist Agness Chindimba, the founder of the Zimbabwe Deaf Media Trust (and is herself deaf), so eloquently put it: “Disability and issues affecting disabled women do belong to the feminist movement. … We cannot afford to leave out other women because they are different from us. At the end of the day, whatever gains the movement may make will not be real and sustainable if millions of other women are still oppressed.”