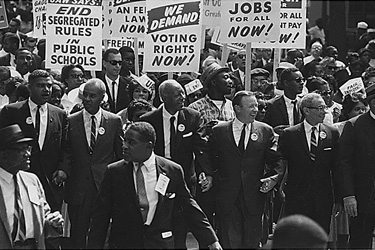

50 Years After the March on Washington, Still Fighting for Jobs and Freedom

As we mark the 50th anniversary of the March on Washington, I can't help but notice that many of the gains made as a result of the Civil Rights Movement are being rolled back.

On Saturday, August 24, tens of thousands of people will descend on the nation’s capital to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the 1963 March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom, the actual anniversary of which is August 28.

There have been some grumblings that the anniversary events will not duly encompass contemporary racial justice issues, and need to do more than re-live the famous images of the past. I am often frustrated with the way racial justice issues for Black people can only be characterized as racist if they somehow reference past symbols of racial violence: legal “lynchings,” the “new Jim Crow,” and Paula Deen’s antebellum-themed summer soiree. The threats to cutting food stamps, the rollback on abortion access (which disproportionately affects poor women), the battles for low-wage workers and teachers, and the various fights over racial profiling in New York City, New Orleans, and Sanford, Florida, are all contemporary issues facing Black people in the United States, and each need their own mass mobilizations here and now.

But what’s past is prologue. Many of the gains made as a result of the Civil Rights Movement are being rolled back, and some of the recent U.S. Supreme Court decisions are great examples of this, demonstrating just how much a constant presence the nation’s racist past remains.

In Shelby County v. Holder, the Court ruled section 4 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965 unconstitutional. Arguing in its decision that “things have changed in the South,” the Court nullified the formula initially created by the act to determine what jurisdictions needed federal “preclearance” before amending “any voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure with respect to voting.”

Critical race legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw told Washington, D.C.’s Afro-American newspaper that the decision was akin to “building a dam to keep the lowlands from flooding and for 40 years the lowlands don’t flood and then deciding that you don’t need the dam anymore.”

But the Court didn’t stop at gutting voting rights. The Supreme Court also ruled in two cases making it more difficult for employees to sue on the grounds of racial discrimination. In Vance v. Ball State University, the Court ruling narrowed the definition of “supervisor” held by the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Essentially, the Court decided that supervisors can only be held liable in a discrimination case if they have power over the hiring, firing, changing of work responsibilities, promoting, or demoting of an employee.

In a second case, University of Texas Southern Medical Center v. Vassar, the Court decided employees must prove that they’ve been denied a promotion or raise only because of discrimination—which gives employers more room to claim a host of other reasons why someone didn’t get a promotion or raise.

Much of the coverage of the Supreme Court decisions this summer focused on those regarding same-sex marriage. Many people were thrilled that the Court declined to rule on the Proposition 8 case (which essentially made a lower appeals court decision in favor of same-sex marriage in California valid), and struck down the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), which made same-sex marriages recognized by the federal government in the states that currently allow such unions. But this ruling is not without racial implications. As American University law professor Nancy Polikoff noted in a statement about the ruling, “[T]he demographics of who marries now is highly skewed by race and class. There is every reason to assume those demographics will hold for lesbians and gay men as well. So we will have same-sex couples who don’t marry, just as we have different-sex couples who don’t marry.”

It is important to note, as Polikoff hinted, that African Americans as a U.S. racial group are the least likely to be married. And even if Black gay and lesbians want to get married, the areas with the highest proportion of Black same-sex couples are in Southern states that have constitutional bans on such unions.

So even looking at the DOMA decision from a kind of “states’ rights” perspective, the situation is still one in which there is a liberalization of laws in states that have fewer Blacks. And the places where Black people reside in great numbers (or are highly concentrated) have the most restrictive voting rules, drug enforcement, and access to social safety-net programs like food stamps and Medicaid, and the least labor protections.

In fact, if we go back one year to the Supreme Court decision on the Affordable Care Act, we see that a vast majority of the states that are not opting in to the expansion of Medicaid (and all the ancillary benefits for community health centers, hospitals, and health-care jobs that come with it) are in the South, with large uninsured Black populations. A recent report by the Kaiser Family Foundation found that because of this, nearly six out of ten African Americans who would have otherwise qualified for the Medicaid expansion in 2014 live in states where they will not receive it.

But despite these legal challenges, it seems clear to me that we are on the precipice of a moment of mass civil disobedience particularly involving Black people, the likes of which we have not seen in decades. From the Moral Monday protests in North Carolina, to the Dream Defenders in Florida taking on gun laws involved in the murder of Trayvon Martin and the prosecution of Marissa Alexander, to teachers and parents in Chicago and Philadelphia getting arrested to prevent school closures, to striking fast-food and Walmart workers, to all the work challenging racial profiling and police violence, from New York City to New Orleans, this may be a historic moment for the Civil Rights Movement of today that is largely being reported by mainstream media as isolated incidents and not a potential turning of the tide.

Though I grow tired of always pinning Black people to the past, I don’t think the Civil Rights Movement has the same level of emotional resonance for young people as it has for some others, and that can actually be a barrier to new forms of organizing, mobilizing, and resistance. But I do think, on August 24 at the National Mall, we have many struggles we’ll be carrying into the future.