Sex And The City: Eww It’s For Girls!

There was no way a two-hour film version of "Sex and the City" would live up to the complexity of the six-series-long show. But did half the characters need to be so flat, and the show's attempt at racial diversity such a misfire?

With a flutter of tulle and a flash of bejeweled stilettos,

women made history this weekend. We showed up at theaters, beat up Indiana Jones, and demanded that our

power as an audience be recognized. If only Sex

and the City: The Movie had lived up to the TV show that inspired the

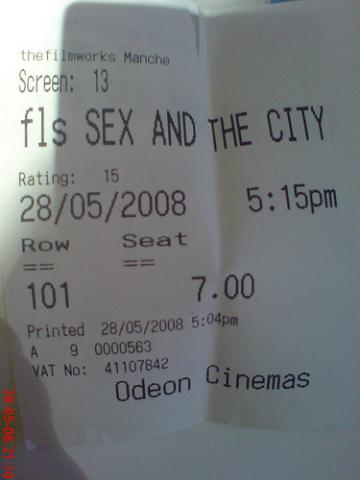

box-office barnstorm. But that’s a tall order — this is Hollywood after all. Photo by Keepin’ On

Photo by Keepin’ On

Of course, the SATC

backlash was underway before the movie premiered: eww,

it’s for girls, the pundits declared. But box office numbers proved the

sexist naysayers beyond wrong. It couldn’t just have been Manohlo-clad,

Cosmo-swilling party gals buying tickets–there aren’t that many of them.

Attendees most assuredly included dudes, moms and daughters, the un-glamorous,

and plenty of feminists.

After all, the show’s brand of feminism was as important to

its success as outlandish outfits and sexual positions. Sex and the City’s

heroines make widely divergent choices ("I choose my

choice!" aspiring housewife Charlotte shouts at working gal Miranda during

one memorable episode). Women viewers know it can be painful in real life for us to face up to those who

live differently, the Charlottes to our Mirandas. SATC allows its characters to

feel the omnipresent judgments and conflicts in women’s lives, and feel them

deeply, in a way that resonates with truths about modern womanhood. But then,

as the arc or episode draws to an end, the four characters always accept each

other. That kind of unassailable sisterhood is a feminist ideal, even when

accented by silly designer shoes.

WARNING! SPOILERS BELOW

Of course, there was no way a two-hour mainstream film would

live up to the complexity of the show, which built these themes into six

seasons and countless storylines. The film’s best moments come after Carrie is

pseudo-jilted at the altar, and our four heroines spend a healthy chunk of time

onscreen together, trading the kind of insight and banter that made the show so

much fun.

Throughout the film, all four stars remind us that they have

real acting chops, but Kim Cattrall as an older, more monogamous, and less

happy Samantha shines the brightest. Samantha’s struggle between her genuine

love for her hunky movie star boyfriend and her desire to be independent and

free is actually quite poignant and multi-dimensional, and gets to the heart of

the show’s themes. And Sam’s biting one-liners break the onscreen tension

without sacrificing emotion, providing the best humor in the film. "Oh, honey, you made a little joke," she says to the

catatonically-depressed Carrie who has shown the energy to muster a bad

pun about her "Mexicoma." Catrall is hilarious, but she also shows how

deeply attuned these women are to each other. (So for everyone who moaned about Catrall

holding out for a better paycheck, she deserved it!). I usually prefer Miranda

to Samantha, but I thought Catrall was given the most subtle and meaty

material, and she tackled it with relish.

As wonderful as it felt to greet Samantha and her crew, and

as much as the audience at my screening laughed, sobbed, and hollered at the

screen, the movie had some big disappointments. The first one, which has been

widely noted, was the subplot with Jennifer Hudson, taking

the "Magical Negro" stereotype to a new level. Hudson, as Carrie’s

assistant Louise, waltzes in, literally helps Carrie clean up her

post-breakdown mess, gives her a special "love" keychain, and then disappears

back to St. Louis once

Carrie doesn’t need her anymore. Despite truly gargantuan acting efforts by

both Sarah Jessica Parker and Hudson during their scenes together, it shocks me

that the producers and writers didn’t try harder to throw some window dressing up around Louise’s

tokenization (memo: it’s not that tough: give her some sex scenes, some talent

beyond organizing white women’s lives), even if they wouldn’t put the effort into turning her character into someone real. But mere window dressing wouldn’t be close to enough. It may have seemed daunting to create three-dimensional secondary

characters in a two hour film, but shouldn’t the filmmakers be smart

enough to realize what an unfortunate pattern they were playing into?

The film’s second significant disappointment was in its portrayal of the characters

of Miranda and Charlotte. Both characters, more realistic New Yorkers than

their counterparts, actually grew during the course of the series. Miranda

transitioned from a too-tough, too-vulnerable go-getter to a more balanced and

happy person, while Charlotte let go of her dreams of porcelain domesticity and

found a nebbishy but beloved husband and an adopted daughter. In light of those histories,

both of these women deserved

better storylines than the film gave them: is Charlotte really beatifically

content with the life of an Upper East Side wife? Can’t Miranda ever be given a

moment to be proud of her achievements without snapping, or being punished, as

a result of them?

It’s no surprise that the movie didn’t live up to the show,

nor is it a surprise that it was such a huge hit anyway. Women, and men of color, are inured to enjoying films with problematic elements, because otherwise we’d

never see movies at all. Despite my own critiques, it was exhilarating to be surrounded by mostly women and hearing the laughter, tears and cheering. Let’s

hope that the triumph of this film, combined with that of Juno, means that there will more smart

movies for women. But more importantly, let’s hope that it gives Sex and the City II, and other movies of

its ilk, license to be more risky, to be more real, and to include racial diversity

that’s more than just a gesture.